Here are the key takeaways from the US employment report for July released Friday:

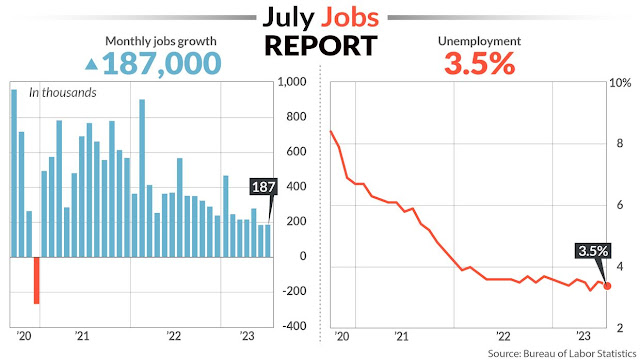

- Employers added 187,000 workers to their payrolls last month, fewer than economists had estimated, and the prior month’s figure was revised down, making it the weakest two months of gains in more than two years.

- As overall job gains slowed, the labor market remains healthy (albeit perhaps too warm for the Federal Reserve’s liking): Wages picked up at a higher rate than forecast, with a 4.4% increase from the year-ago period. The unemployment rate fell and remains near the lowest in decades. Participation remained at 62.6% for the fifth straight month.

- There were signs of cooling throughout the report, though Temporary help services continued their slide, average hours worked ticked down, and some categories that led the boom in job growth in the post-pandemic period continued to cool, including manufacturing and transportation/warehousing.

- Where does this leave the Fed? With some room to wait for signals from other data before their September meeting. Friday’s report showed a labor market that is cooling, which works in policymakers’ favor, but wage inflation is still about double what the Fed thinks is healthy. Now we await next week’s consumer price index report.

- After some initial volatility, stock futures headed higher and Treasuries rallied, suggesting a soft-landing interpretation of the figures. The S&P 500 was up 0.4% as of 9:31 a.m. in New York. Treasury 2-year yields, sensitive to imminent Fed moves, fell four basis points to 4.84% while the dollar retreated.

The July jobs growth in the United States fell short of expectations and was revised lower for the previous two months, signaling a cooling of the labor market after nearly 18 months of interest rate increases. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported an addition of 187,000 new non-farm jobs, slightly below the forecast of 200,000. June's figure was revised downward to 185,000, and May's figure was adjusted to 281,000. While these numbers could be seen as a positive development indicating progress in the Federal Reserve's fight against inflation, concerns about wage growth persist. The overall labor market, however, remains robust, with the unemployment rate dropping to 3.5 percent. Hourly earnings saw stronger than expected growth at 4.4 percent year on year, surpassing the levels consistent with the Fed's 2 percent inflation target. Additionally, wages grew 0.4 percent month on month, exceeding consensus forecasts of 0.3 percent. Despite these encouraging signs, economists, such as Andrew Patterson from Vanguard, caution that wage growth remains a concern and that the Federal Reserve is unlikely to become complacent. The health of the labor market is closely monitored by the Fed and investors since wages and job growth significantly impact inflation. While recent data showed a decline in consumer price inflation and the Fed's preferred indicator, the personal consumption expenditure index, dropping to its lowest level since March 2021, the Fed has warned that strong labor market conditions may hinder efforts to bring inflation down to its target. Some economists, including Agron Nicaj from MUFG, believe that recent inflation numbers have been overly optimistic and expect elevated inflation as long as consumer spending remains high and the labor market remains strong.

In July, the healthcare, financial services, and wholesale trade industries experienced significant job gains, while manufacturing employment decreased by 2,000. A survey conducted by the Institute for Supply Management indicated a contraction in activity within the politically significant manufacturing sector. Economist Agron Nicaj noted that although July's decline in manufacturing employment falls within the margin of error and should be treated as essentially flat, several indicators suggest that this industry may be one of the first to consistently experience negative employment growth.

In response to the weaker job growth, the Federal Reserve recently raised interest rates to their highest level in 22 years and expressed the possibility of further increases if deemed necessary. However, futures markets indicate that most investors believe the central bank will maintain steady rates for the remainder of the year. As of Friday morning, there was only a 17 percent chance of a rate hike at the Fed's next meeting in September, and approximately a 37 percent chance of at least one rate increase by November. These probabilities were relatively unchanged compared to before the release of the jobs data.

Following the release of the jobs data, bond markets rallied as investors weighed the weaker job figures against the stronger unemployment rate. Consequently, the 10-year Treasury yield experienced a decline to 4.12 percent, representing a 0.07 percentage point drop for the day. Meanwhile, stocks showed modest gains, with the S&P 500 up 0.3 percent in early trading.

When storms hammered California's farms last winter, Kevin Kelly knew his small factory outside San Francisco would soon see demand wilt for the plastic bags it churns out for pre-cut salads and other produce.

In the past, he would have swiftly chopped 10% of the workers that run his bag-making machines or about 15 people.

But after struggling to fill jobs during the boom triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, he didn't this time. "I knew it would be hard to find people when business came back, let alone train them," said Kelly, the CEO of Emerald Packaging. So he held on to his employees and found ways to curb their hours, including cutting overtime.

Employers across the U.S. are making a similar calculation. Faced with the tightest job market in decades, many have become less trigger-happy with layoffs, even in the face of a cooling economy. Indeed, a monthly report from outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas on Thursday showed that announced layoffs hit their lowest level in nearly a year last month as companies were "weary of letting go of needed workers."

It's unclear whether this strategy - dubbed labor hoarding by economists - would endure if the economy slipped into a deep recession, as some have predicted it would after the Federal Reserve embarked last year on an aggressive campaign to raise interest rates to curb high inflation.

But, so far, the economy has continued to grow, albeit more slowly, and the job market has powered onward. The U.S. jobless rate edged down to 3.5% last month, the Labor Department reported on Friday, up only slightly from more than a half-century low of 3.4% earlier in the year.

'HOLD ONTO YOUR LABOR FORCE

At least one major company has adopted a formal strategy of hoarding workers.

Speaking to investors last December, Alan H. Shaw, the CEO of Norfolk Southern, said part of a larger strategy aimed at making the railroad company more competitive with trucking would be to avoid the cycle in which workers are furloughed during downturns and then rehired when the economy improves. Shaw said difficulties bringing back workers hurt the Atlanta-based firm's ability to serve customers during the pandemic boom.

The strategy is being put to the test now, as rail volumes have fallen back to earth after that boom ended. "But we're continuing to hire," Shaw told Reuters this week, "because we have confidence in the U.S. economy and the U.S. consumer."

While many companies aren't hiring at the heated pace they were a year ago, they're also not yet rushing to thin the ranks.

U.S. job openings fell to the lowest level in more than two years in June, according to the monthly Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS report, released by the Labor Department this week, but they remained at levels consistent with a tight labor market. Layoffs and involuntary separations hit a six-month low.

"There's a lot of hoarding going on - and still lots of hiring in industries that are experiencing strong demand," said Dana Peterson, the chief economist at the Conference Board in New York.

The group's latest survey of CEO confidence, done in conjunction with the Business Council and released on Thursday, found that while business leaders continue to prepare for a downturn, the fight for workers remains fierce. Forty percent of the CEOs said they plan to increase hiring in the next 12 months, while another 40% intend to maintain the size of their workforce.

The survey showed most CEOs expect the next downturn to be short and shallow. "If that's the case," said Peterson, "it makes sense to hold onto your labor force."

LAYOFF REGRETS

Arnold Kamler, the CEO of Kent International, learned that the hard way. Demand for the bicycles that the company imports and manufactures at a small factory in South Carolina was insatiable during the pandemic. But as lockdowns eased, bike sales evaporated, and inventories piled up in the company's warehouses and even in corners of its factory.

He laid off 60% of the workers at the company's South Carolina plant at the end of last year but now regrets it.

"I thought that when we went to rehire in March, we would have no problem ramping up," he said. But only about a third of the workers returned and the company is now scrambling to find and train new employees. The factory currently has 85 workers, but Kamler would like 110.

Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter in Los Angeles, said employers tell her they are retaining workers they wouldn't normally keep because of concerns they will have problems ramping up. But she sees a limit to this. "I don't think it's the case that many businesses are holding onto workers who are idle," she said.

Thomas Simons, senior U.S. economist at Jefferies, has argued for months that at some stage the need for businesses to recapture margin will outweigh the argument for retaining under-used staff as a hedge against the difficulty of later rehiring. But that "view is becomingly increasingly difficult to defend," he said last week after data showed weekly new claims for unemployment benefits hit their lowest level since February. Data released on Thursday showed weekly jobless claims rose slightly in the latest week.

Meanwhile, at Emerald Packaging, the business has recovered from the slowdown caused by the winter storms.

"We're actually making more money now than when demand was skyrocketing," Kelly said because surging prices for raw materials such as plastic resins cut into profits during the boom.

And for now, the company is continuing to hire. "We're still 15 to 18 (people) short," he said.

America’s job market is cooling. It isn’t cool enough for the Federal Reserve just yet, but it is getting there.

The Labor Department on Friday reported that the economy added a seasonally adjusted 187,000 jobs in July from a month earlier—fewer than the 200,000 that economists polled by The Wall Street Journal expected. It also revised the previous two months’ job gains lower.

Even so, the unemployment rate, which is based on a separate survey from the job figures, slipped to 3.5% in July from 3.6% in June. That underscores a simple fact: The pace of job gains is probably still far too fast to prevent the unemployment rate lower in the months ahead. And if the unemployment rate falls, it will reinvigorate worries over wage inflation, which could lead Federal Reserve policy makers to raise rates even more.The right pace of job growth, however, is hard to figure out.

If you go by projections the Labor Department released last fall, it looks as if job growth needs to slow markedly. In those, the U.S. labor force gains a total of about 1.36 million workers this year and next. For it to do that and maintain an unemployment rate of 3.5%, the economy could gain an average of only around 55,000 employees each month. Moreover, this is a somewhat more expansive measure of employment than the one used for the main monthly jobs numbers—it includes farm employment, for example—so shave even that figure a smidge.

The good news is that those projections look as if they might have been too cautious on two counts: The number of people immigrating to the U.S., and the share of the population that is in the labor force.

Immigration into the U.S. has bounced back. This is partly because President Biden’s immigration policy is less restrictive than former President Trump’s, but it is also because the pandemic provoked a crash in immigration. Since then, there has been a rebound. Census Bureau figures show that, in the year ended July 1, 2022, the U.S. population grew by about 1.3 million people from the prior period after adding only about 520,000 in the year ended July 1, 2021. Most of that came as a result of a pickup in net immigration, which added about 1 million people to the population, a Brookings Institution analysis shows, after adding only about 376,000 the prior year.

Indeed, the Labor Department in February adjusted its population estimates higher. That also resulted in an addition of 871,000 people to its labor force estimate—that is, the number of people who are employed or actively looking for a job. It upped its population estimate when it made its population adjustments the prior year, and, if immigration continues at its recent pace, it might be releasing upward adjustments again next February.

A larger share of the working-age population than the Labor Department projected has been working. That, too, is a plus. It projected a labor-force participation rate of 61.5% for this year, but Friday’s report showed the participation rate stood at 62.6% last month.

The participation rate is still below the 63.3% it held before the pandemic and well short of the peak of 67.3% it hit in early 2000. One issue here is that, in an aging country, retirees are making up an ever-increasing share of the population. But lately counteracting that force has been a pickup in the so-called prime-age participation rate—that is, labor-force participation among people aged 25 to 54. Last month it was 83.4%, which was better than it was just before the pandemic.

In the late 1990s, it averaged 84.1%, though. Arguably it could take out that old peak. First, among women, prime-age labor-force participation has been rising but is still short of the level in other countries, such as Japan, which suggests there is scope for further increases. Second, a far greater share of the prime-age population have college degrees than in the 1990s, and higher education levels tend to coincide with higher participation.

The upshot is that while job growth might still need to slow more to convince the Fed to ease up on rate increases, it might not need to slow that much more. The economy can probably handle more jobs than some people feared.

In July, the economy added 187,000 jobs, including gains in health care, social assistance, financial activities, and wholesale trade. https://t.co/YhLEuaacSN #JobsReport pic.twitter.com/kPJiYk5v96

— U.S. Department of Labor (@USDOL) August 4, 2023