I’ve been thinking about labor and the holiday meant to celebrate our nation’s workers. My observation: “Labor” Day is a ruse, just as “hero” is a moniker typically attached to someone we’ve decided to underpay — teachers, front-line workers, etc. A more honest name for a holiday describing who/what we value would be “Capital” Day.

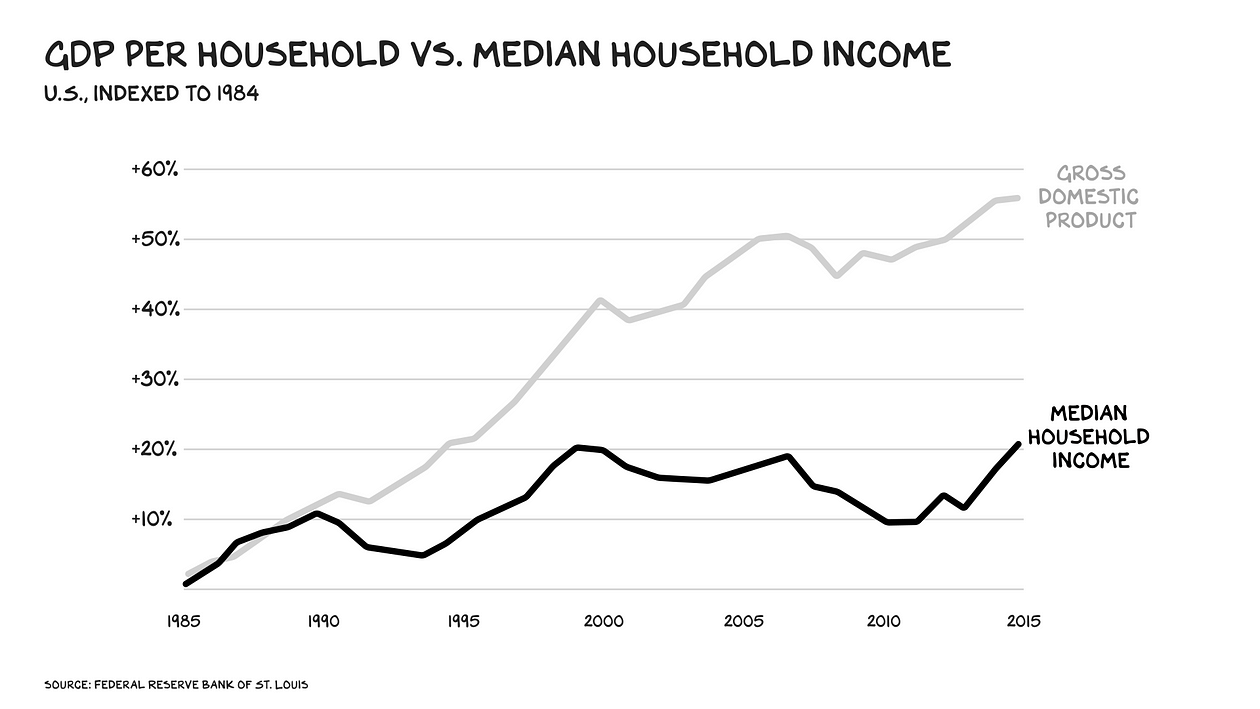

We don’t honor workers, we throw loaves of bread at them and give them circuses to distract them from their servitude to capital, which captures more of the spoils each year. Over the past five decades, U.S. GDP growth has outpaced wage growth by 63% — in years prior, GDP and wages expanded at the same rate. In 1970 the American middle class received 62% of the country’s aggregate income; today it’s 42%. The top 1% now owns 32% of our nation’s wealth, and the bottom 50% owns 3%. America has never been so disdainful of its workers.

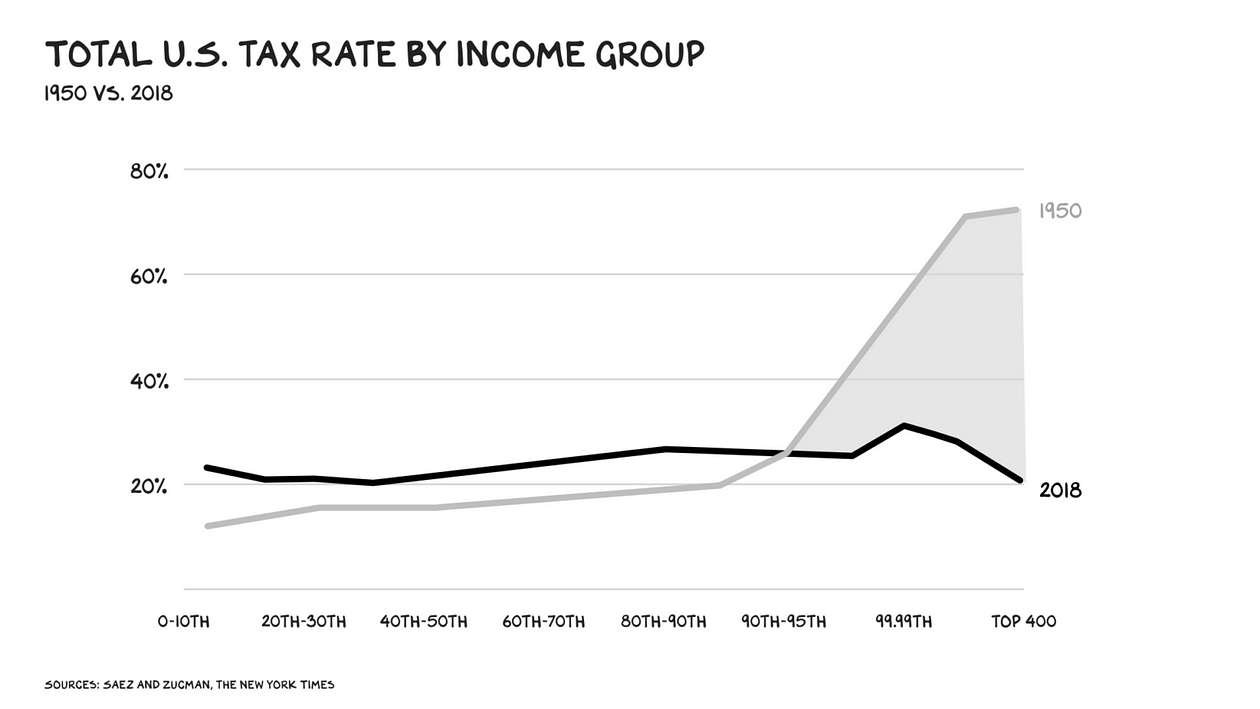

I discuss this in my forthcoming book, Adrift: America in 100 Charts. (You can pre-order it here.) It’s the story of our nation told through (wait for it) charts. It covers a lot of topics, but the common thread is that our middle class is dying — largely because of a purposeful, decades-long transfer of power from labor to capital. There was a time when 30 years of hard work got you the American Dream: homeownership, college-educated children, retirement, and greater economic security than your parents. No longer. Today economic security is defined by the assets you already possess. We impose harsher taxes on income gains (i.e. the fruits of labor) than on capital gains and reward high-net-worth individuals with tax loopholes and bailouts. America is no longer the best place to get rich, but to stay rich.

Anyway … this week I’ve been thinking about labor. What it means, who performs it, and how the holiday can register real meaning again.

Unions

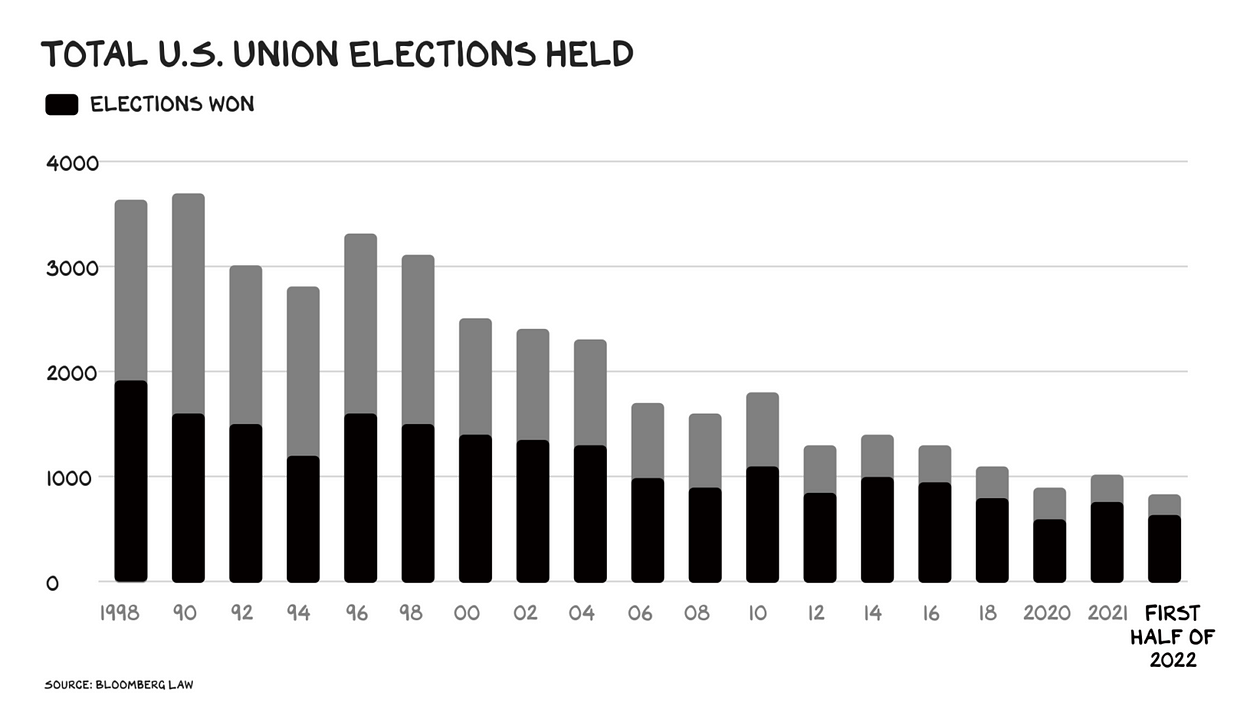

Unions are making positive headlines recently. Some Starbucks workers organized in December. Amazon workers followed in April. So far this year, unions have won 641 elections (the most in nearly two decades) with a 77% win rate (the highest percentage on record). Almost 80,000 American workers have gone on strike in 2022 — three times as many as in the same period last year. Meanwhile, U.S. approval of labor unions is at its highest level since 1965. By the looks of it, unions are making a comeback.

People will say these wins for unions win for workers. Maybe. However, in my view, this is a dead cat bounce. Over the past several decades, unions have proven they don’t work.

As Rani Molla wrote, forming a union is the easy part. The hard part is negotiating a contract with the employer. Companies deploy various methods to ensure there is almost never an agreement with the union — usually just stalling. After Amazon’s Staten Island workers voted to organize, Amazon buried them in paperwork. Starbucks did the same. Almost a third of unions don’t reach an agreement within three years. Proving to the National Labor Relations Board (the agency that enforces labor law) that a company is unnecessarily stalling is difficult. And even if you do, per Rani … “there’s not much it can do.” So the union gets tired and discouraged, the employees inevitably turn over, the effort bleeds out, and the company marches on sans union.

In many ways, the union is the corporation’s perfect enemy: disorganized, inexperienced, underfunded, and understaffed. “I want to work for the United Auto Workers union,” said no ambitious college graduate ever. It’s not a coincidence that, despite the recent uptick in union formation, union membership is in freefall.

One Union, for All Workers

The need for labor representation remains, however. The balance of power between capital structurally favors capital. Capital has, well, the capital — to hire lobbyists and public relations teams, lawyers and strikebreakers, to outwait workers who need their paychecks to put food on the table. You don’t need to be a labor economist to see this, just review the past 50 years in America. And it’s likely to get worse: automation is projected to put nearly 40% of American jobs at “high risk” by the early 2030s. We already let offshoring decimate a generation of American labor, we have a moral and economic obligation to better manage this greater transition. But if not labor unions as we know them, who?

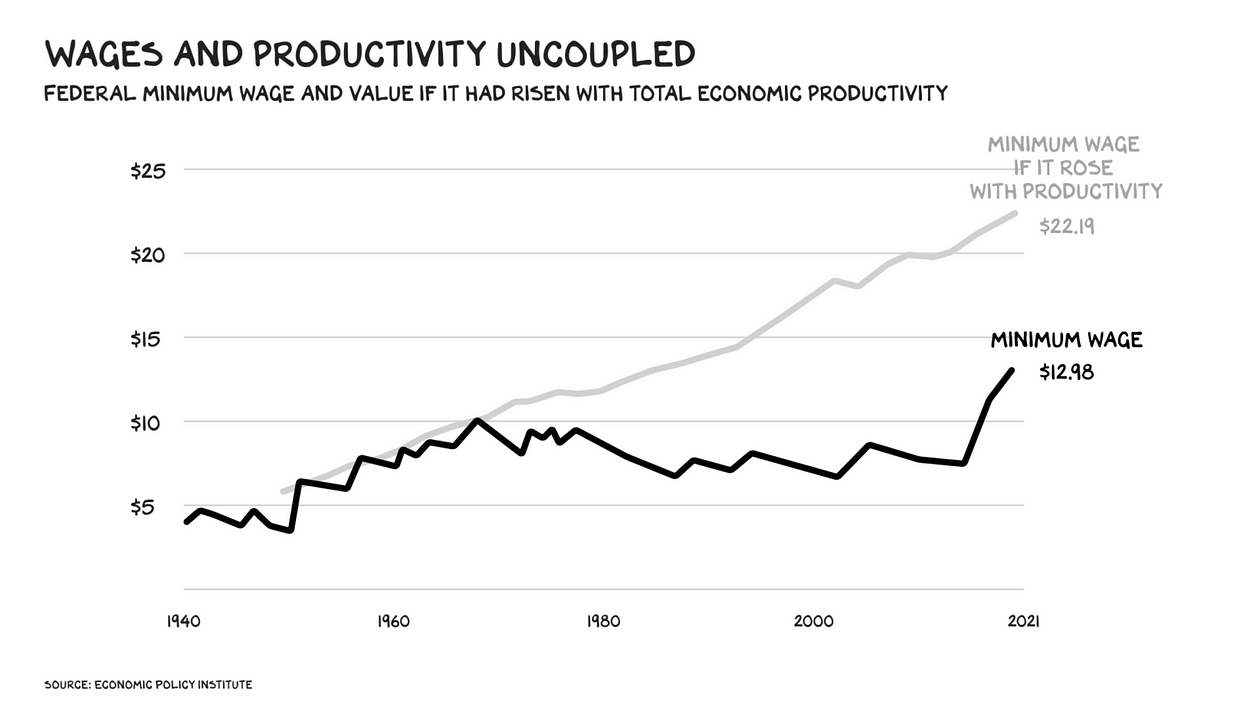

There should be one union: the federal government. Unlike small, fragmented groups of workers, this is a force to be reckoned with — and companies must comply with its demands. It should demand more. Dignity in work, for starters. The right to not be sexually harassed or discriminated against is a good thing, but it’s a floor. In America, the wealthiest nation in the world whose corporations are registering the greatest profits in history, you can still work full time and fall below the poverty line. We must raise the minimum wage, dramatically. If the federal minimum wage had risen at only the same pace as U.S. productivity since 1960, it would be three times what it is today. A $20-plus federally mandated minimum wage would send some consumer stocks down and make many small businesses unviable. It would also be worth it.

Workhorse

We often talk about income inequality, the top 1% vs. the 99%, and we should. But there’s another cohort that’s rarely discussed, whose workers on an effort-adjusted basis may be the biggest losers re changes to the tax code: the 90th-99th percent.

Lawyers, doctors, accountants. Smart, ambitious, hard-working, college-educated people who’ve played by the rules and done everything right. While the media often buckets them in with the top 1%, many are actually struggling — but they’re too embarrassed to complain about it.

A lawyer living in San Francisco making $350,000 a year likely pays 49% of their income in federal and state taxes. Most “workhorses” need to live in a high-cost urban area (the average home in San Francisco costs $1.5 million), and things are likely tight. This is not a sob story — many Americans would kill for these problems. However, we’re being heavy-handed with the wrong people, as many could build real wealth and make the jump to lightspeed if we returned to a progressive tax system that charged the same rates on the top 1%. The asymmetric upside is reserved for the ultra-wealthy — accounting for capital gains tax, they pay lower tax rates than the 90th-99th percent. We have opted for a regressive tax system.

Care Work

When we discuss labor, we almost exclusively talk about paid labor, the work we do for money. But there is an enormous, critical swath of labor this view overlooks, and it’s important to work: caring for one another. Raising our kids, administering to the sick, and caring for the aging.

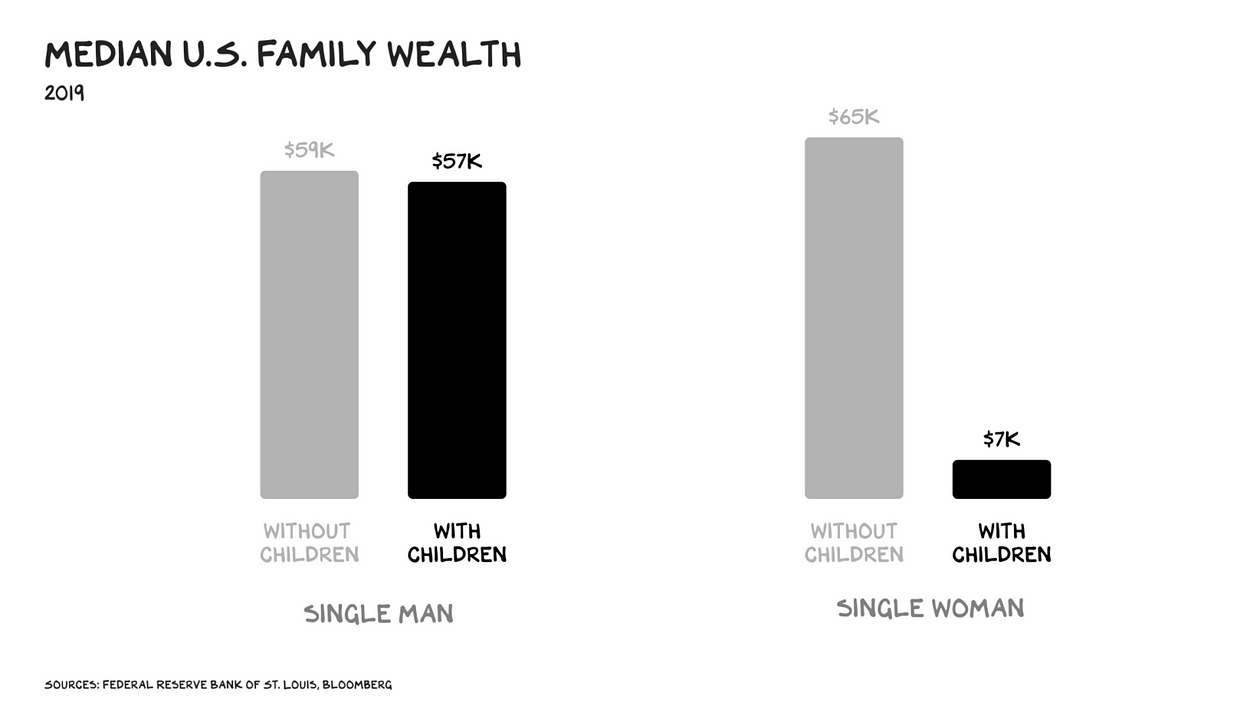

A good measure of a society is how well it provides for its weakest members. It’s also a good predictor of a society’s future. A poor system for raising children is a recipe for future failure. What’s our system? We turn to women. Among solo-parent households, 82% are headed by single mothers. When it comes to the elderly, 61% of caregivers are women, and they are much more likely to be the primary caregiver.

Besides the inequity, our assumption that mom will take care of things is brittle. Covid illuminated how brittle. Students fell four months behind in school, and reading and math scores sank by the sharpest margin in three decades. The gender gap in employment and labor participation increased, and a quarter of mothers said they had to either stop working or work less.

In some distant past, when people lived in extended family units, with three or four generations under one roof and a dense network of siblings and cousins ready to pitch in, an “informal” system of caregiving — i.e. no system at all — might have been viable (though it was rarely fair between genders). But that’s not how our society works today, and more importantly, that’s not how we want it to work. Mobility and migration are the unlock that have powered a century of innovation, but they mean we need to support people as they care for those who need support.

This is the role of government. It is neither feasible nor fair to expect employers (the paying kind) to abandon their competitive advantage and unilaterally support a societal good. Yet our existing protections for caregivers are deficient. The U.S. is one of only six countries that doesn’t offer paid family leave. The others? Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga. This is bad company. Every other developed nation provides substantial paid family leave, with the average OECD country offering more than 17 weeks.

The Biden administration tried to advance another much-needed policy to support family care work, the child tax credit. This is something I’ve long advocated for, inspired by Senator Michael Bennet. When we instituted this program on a temporary basis during the pandemic, we kept 3.7 million kids out of poverty and cut hunger by 25%. This was a massive win: child poverty is a scourge and its costs on society compound over a lifetime. But the Democrats were forced to strip a provision extending the credit from the Inflation Reduction Act, after Joe Manchin (and, to be fair, the entire GOP caucus) refused to go along. Maybe next year.

The rise of remote work and new flexibilities in employment will allow us to do more. I believe we need to explore additional employment protection that gives people who care for others rights in flexible work arrangements. If working from home enables a single parent to stay in the workforce, that’s a win for society. Temporary part-time status and flexible schedules can match our needs to our resources. We should incentivize companies to make this happen and level the playing field so they’re not at a competitive disadvantage when they do so.

As always, the criticism of taxpayer support for care work is the cost. However, we spent $800 billion bailing out corporations with PPP loans while offering $1 trillion in tax breaks per year in the form of loopholes. No government agency can provide a good level of care, more efficiently, than a loved one. We need to arm citizens with the resources to care for loved ones.

A substantial increase in the minimum wage, restoration of a progressive tax system, and greater flexibility for caregivers starting with paid family leave. There’s nothing wrong with America that can’t be fixed with what’s right with America. And Americans like to work. All of these efforts would come at a cost, and it’s likely the stock market would go down. But putting more money in the hands of middle-class Americans has one key advantage: They spend it.

Loneliness, stressed young families, a lack of connection, class warfare, and the draining of meaning. All of these things plague America. There is no silver bullet. But there is something we can do to help address all of them. We can work.