The U.S. economy created far more jobs than expected in January despite the disruption to consumer-facing businesses from a surge in COVID-19 cases, pointing to underlying strength that should sustain the expansion as the Federal Reserve starts to raise interest rates.

The Labor Department's closely watched employment report on Friday also showed job growth in December and November was stronger than initially estimated. The upbeat report ended days of anxiety among economists and White House officials who had frantically tried to prepare the nation for a disappointing payrolls number.

"It confirms that each successive wave of the virus is having a smaller and smaller impact on activity and labor demand," said Brian Coulton, chief economist at Fitch Ratings.

Nonfarm payrolls increased by 467,000 jobs last month, the survey of establishments showed. Data for December was revised higher to show 510,000 jobs created instead of the previously reported 199,000. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast 150,000 jobs would be added in January. Estimates ranged from a decrease of 400,000 to a gain of 385,000 jobs.

Part of the broad increase in payrolls likely reflected low layoffs after the holiday hiring season because of worker shortages. Actual employment in January typically falls, but the model used by the government to strip out seasonal fluctuations from the data accounts for this by adding about 3 million jobs to produce the seasonally adjusted figure.

The government also reported that 374,000 more jobs were created in the 12 months through March 2021 than previously reported. The labor market resilience could alter expectations that economic growth would slow significantly in the first quarter after robust growth in the fourth quarter.

It also clears the way for the U.S. central bank to raise interest rates in March to tame high inflation. Economists expect as many as seven rate hikes this year.

Economists had been bracing for a weak jobs report as the government surveyed businesses for payrolls in mid-January when Omicron infections were peaking. The Labor Department estimated that 3.616 million people who had a job were not at work during the survey week because of illness.

Workers who are out sick or in quarantine and do not get paid during the payrolls survey period are counted as unemployed in the establishment survey even if they still have a job. Lower-paid hourly workers in industries like healthcare as well as leisure and hospitality, who typically do not have paid sick leave, bore the brunt of the winter COVID-19 wave.

According to the latest government data, paid sick leave was available to 79% of civilian workers in March 2021.

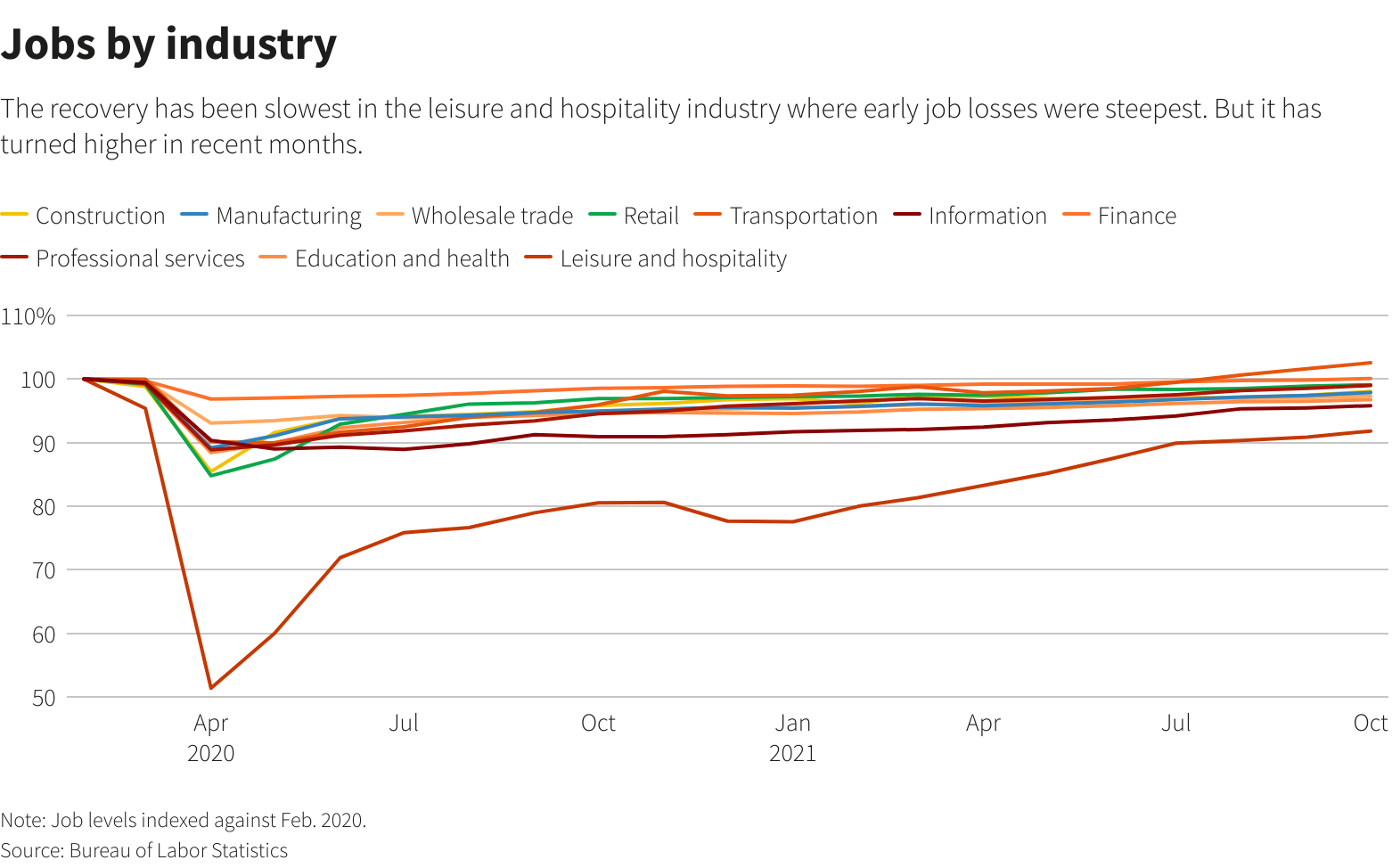

The leisure and hospitality industry added 151,000 jobs in January. Healthcare employment increased by 18,000. There were gains in retail, professional, and business services employment as well as transportation and warehousing, and wholesale trade. Manufacturing payrolls rose by 13,000, but construction employment fell by 5,000, likely because of freezing temperatures.

U.S. stocks were mixed in early trading while the dollar (.DXY) rose against a basket of currencies. U.S. Treasury prices fell.

WAGES SURGE

Employment could increase further as coronavirus infections continue to subside. First-time applications for unemployment benefits dropped for a second straight week last week, retreating further from a three-month high touched in mid-January, the government reported on Thursday.

The United States is reporting an average of 354,399 new COVID-19 infections a day, sharply down from the more than 700,000 in mid-January, according to a Reuters analysis of official data.

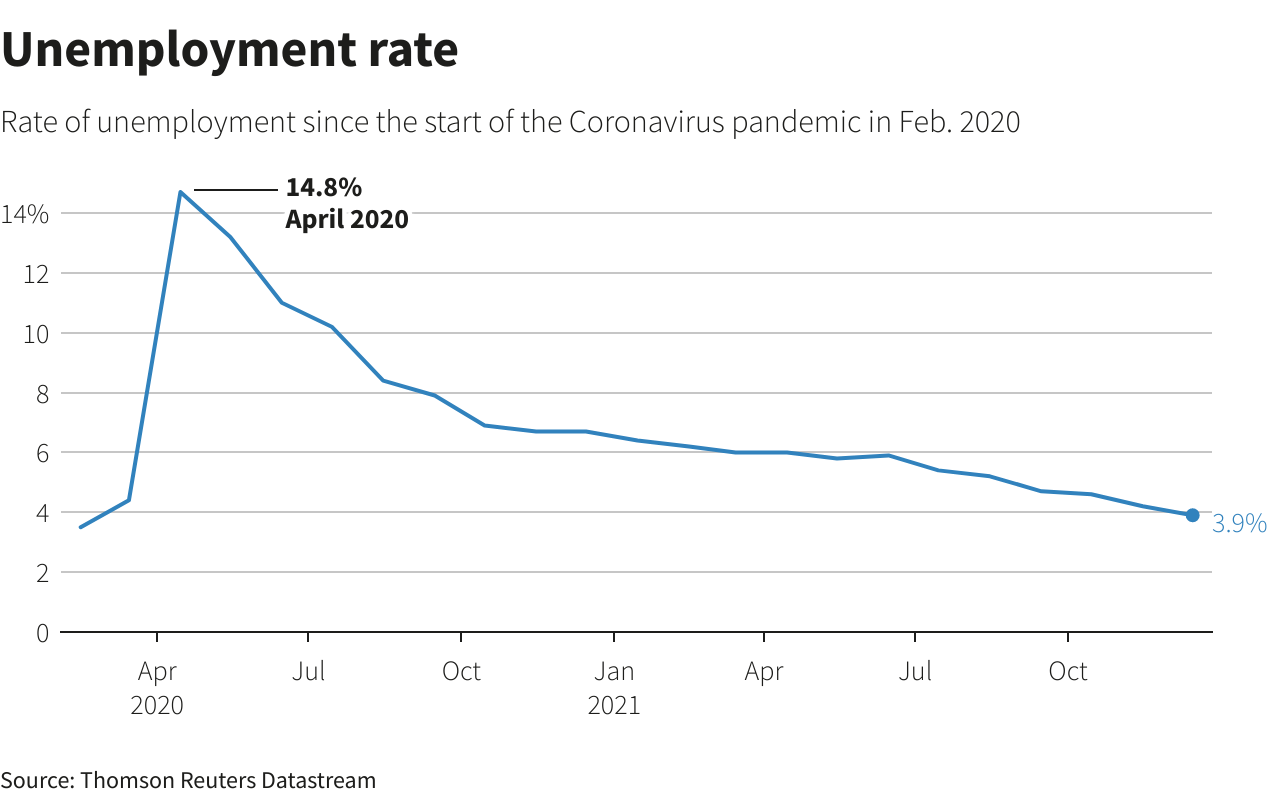

The government introduced new population controls for the household survey, from which the unemployment rate is derived. The jobless rate was at 4.0% in January. The new population assumptions caused a break in the series.

January's jobless rate and other ratios from the household survey are not directly comparable to December. The labor force participation rate, or the proportion of working-age Americans who have a job or are looking for one, was at 62.2%.

With some lower hourly-paid workers at home, wage growth accelerated in January. Average hourly earnings increased 0.7%, which raised the annual increase to 5.7%.

As the US economy reopened, the jobs came back — but the workers have not. At the end of last year, there were almost 11mn unfilled openings, yet the unemployment rate is just 3.9 per cent. With labor scarce, wages are rising their fastest in decades. The disappearing worker is a big factor in the Federal Reserve’s turn to tighten. As officials debate how much and how quickly to restrain credit, I would urge caution. There’s no mystery to the labor shortfall and many of the missing will return. The Fed must calibrate policy to a workforce largely in cyclical, not structural, change. The labor force participation rate is 1.5 percentage points below its pre-pandemic level: a shortfall of roughly 3.5mn workers. The robust wage increases of the past year have been insufficient to pull these workers off the sidelines and back into the “pool of available labor”. The biggest reason is Covid. Between December 29 and January 10, the Census Bureau reported a record 8.8mn people weren’t working because they were caring for someone with Covid or had symptoms themselves. Caretaking responsibilities have disproportionately fallen on women and with schools closed and employment in daycare, nursing, and residential care facilities down at least 10 per cent since early 2020, this is likely to continue. But in the long term, care responsibilities should abate and many should return to the labor force. Participation should also improve as households’ financial cushions wear thin. Fiscal stimulus injected roughly $2.5tn of excess savings into the economy, but the personal savings rate is now lower than before the pandemic. According to research from the JPMorgan Institute, the lowest-income households benefited most from stimulus measures but also burnt through them fastest. Many voluntarily absent workers will soon seek a paycheque. There has also been a sharp rise in retirements during the pandemic. The economy’s reopening should have pulled some back to work but that hasn’t happened yet, perhaps because of Covid fears and bigger nest eggs thanks to soaring equity and housing markets. As the virus abates, many of these people are young enough to return to work. Mental health issues are also keeping workers on the sidelines. According to Mind Share Partners, 50 per cent of respondents said they’ve left roles for mental health reasons, up from 34 per cent in 2019. As the stress of the pandemic eases some should be able to come back. Of course, once the pandemic has subsided, long Covid will still be a problem. The Brookings Institution estimates there are roughly 1mn Americans not working at all due to long Covid, and around 2mn more who have reduced their hours. This amounts to over 1.5mn full-time equivalent workers, nearly 15 per cent of the country’s unfilled jobs. We don’t know how many will recover and go back to work, or be permanently lost to the labor force. Aside from Covid, a drop in immigration to the US has limited the number of available workers. There are 2mn fewer working-age immigrants in the US relative to the pre-pandemic trend. This has been driven mostly by increased restrictions on immigration put in place by Donald Trump’s administration. That is expected to change under Joe Biden. Finally, the cure for high wages is high wages. As incomes rise, particularly for lower-paid jobs, that should in turn attract more people into the labor force. Yet the Fed should take care in how much and how quickly it raises interest rates. Normally, higher rates would result in a rise in unemployment, as cooling demand leads companies to shed workers. That is not what the post-Covid economy needs. Workers will come back, and that should ease wage inflation pressures.