The U.S. economy generated 517,000 jobs in January, a surprisingly strong number that underscores the remarkable resilience of the labor market but could stiffen the Federal Reserve’s determination to squeeze the economy to fight 40-year-high inflation.

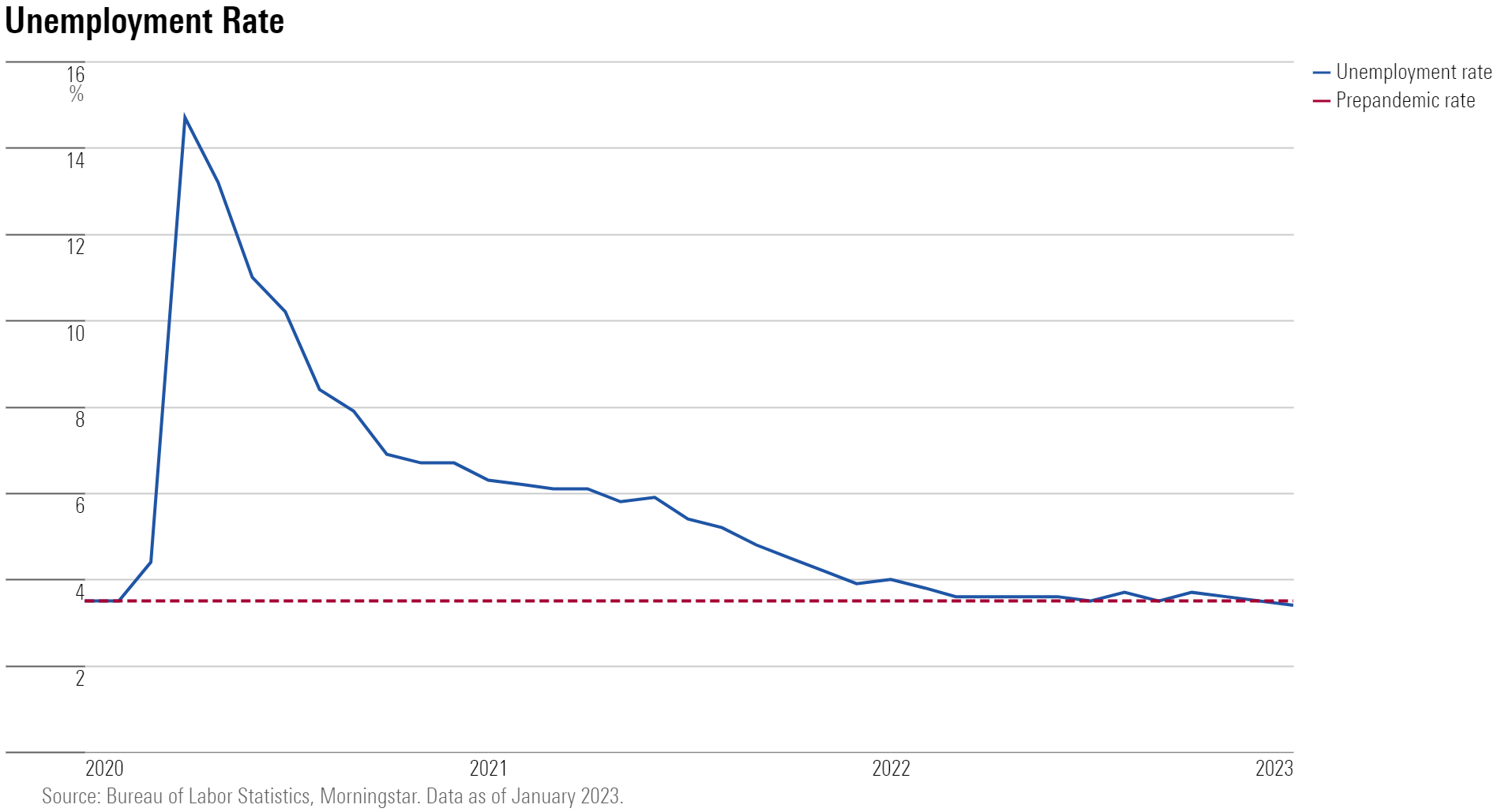

The unemployment rate fell to 3.4 percent, the lowest in more than a half-century, the Labor Department reported Friday.

The number blew away the Wall Street consensus of 190,000 jobs and suggests that the Fed’s efforts to cool the labor market by hiking interest rates at the fastest pace in decades are not yet having the desired impact.

President Joe Biden celebrated the report as evidence the economy is continuing to hum along, and the number is likely to blunt attacks from Republicans over the administration’s spending policies. But senior officials in the West Wing were privately hoping for a less-robust number. So was Fed Chair Jerome Powell.

Here’s how the number is likely to play with four key political and economic figures.

Biden — The White House can view the report as evidence that economists’ predictions of an imminent recession are off-base. But inflation is Biden’s biggest enemy in the economy, and the report will cause some unease within the administration, given that it could mean the Fed will crack down harder on growth to curb prices.

Still, the report clashes with the expectations of many economists and Wall Street CEOs that the U.S. will fall into a recession this year. And it was quickly embraced by Biden’s allies. “Sometimes good news is just good news,” outgoing White House chief of staff Ron Klain emailed POLITICO. “And this time it’s great news.”

Biden often describes the recent slowdown in job growth that preceded Friday’s number as a good thing as the economy transitions from the rapid Covid-19 come back to a period of what he calls more “steady and stable growth.

Senior White House aides have said they are happy with declining numbers — as long as they stay positive — making it easier on the Fed to end the rate increases as soon as possible. They believe the decline in inflation is already well underway, with consumer price growth slowing for six straight months.

But Biden took a victory lap, arguing that the report shows his policies are working.

“For the past two years, we’ve heard a chorus of critics writes off my economic plan,” the president said in remarks before leaving the White House for a trip to Philadelphia. “They said it’s just not possible to grow the economy from the bottom up and the middle out,” he said. “Today’s data makes crystal clear what I’ve always known in my gut: These critics and cynics are wrong.”

Nick Bunker, head of economic research at Indeed Hiring Lab, said that while Friday’s report will get a lot of attention, we’ve been seeing “a juggernaut of the labor market” for several months.

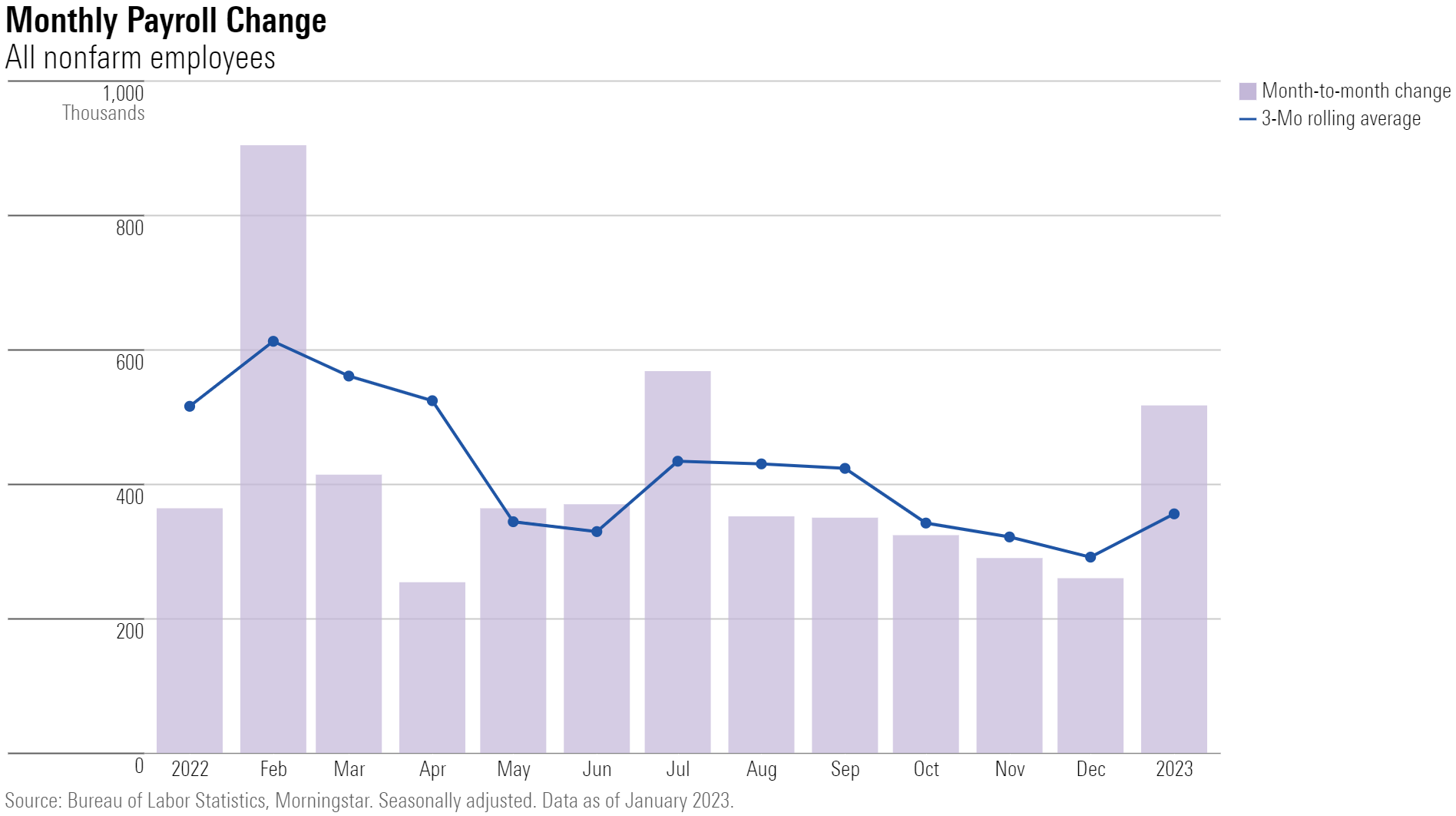

“Employers have added an average of 356,000 jobs a month over the past three months, and the unemployment rate dropped to a level not seen since before Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon,” he wrote in a note. The economy added a robust 4.8 million jobs in 2022.

Powell — The report is likely to come as a jolt to the Fed chair. Powell said in a recent speech that the economy only needs to gain about 100,000 net jobs a month to keep up with the number of new people entering the workforce.

He’s strongly committed to bringing inflation to the central bank’s target range of 2 percent. Since the Consumer Price Index peaked last June at 9.1 percent, inflation has steadily fallen, hitting a still-high 6.5 percent in December.

Powell and the Fed on Wednesday again raised rates by a quarter of a percent, the eighth straight increase. But it was the smallest bump since March. He cautioned at his press conference that more hikes lay ahead, saying “the job is not fully done.”

Any single report can be an outlier and is unlikely to sway the Fed. But Powell is worried about the hot jobs market driving up wages, and fueling inflation. So any news showing the market heating rather than cooling could be unwelcome.

“My base case is that the economy can return to 2 percent inflation without a really significant downturn or a really big increase in unemployment,” Powell said Wednesday. “I think that’s a possible outcome. I think many, many forecasters would say it’s not the most likely outcome, but I would say there’s a chance of it.”

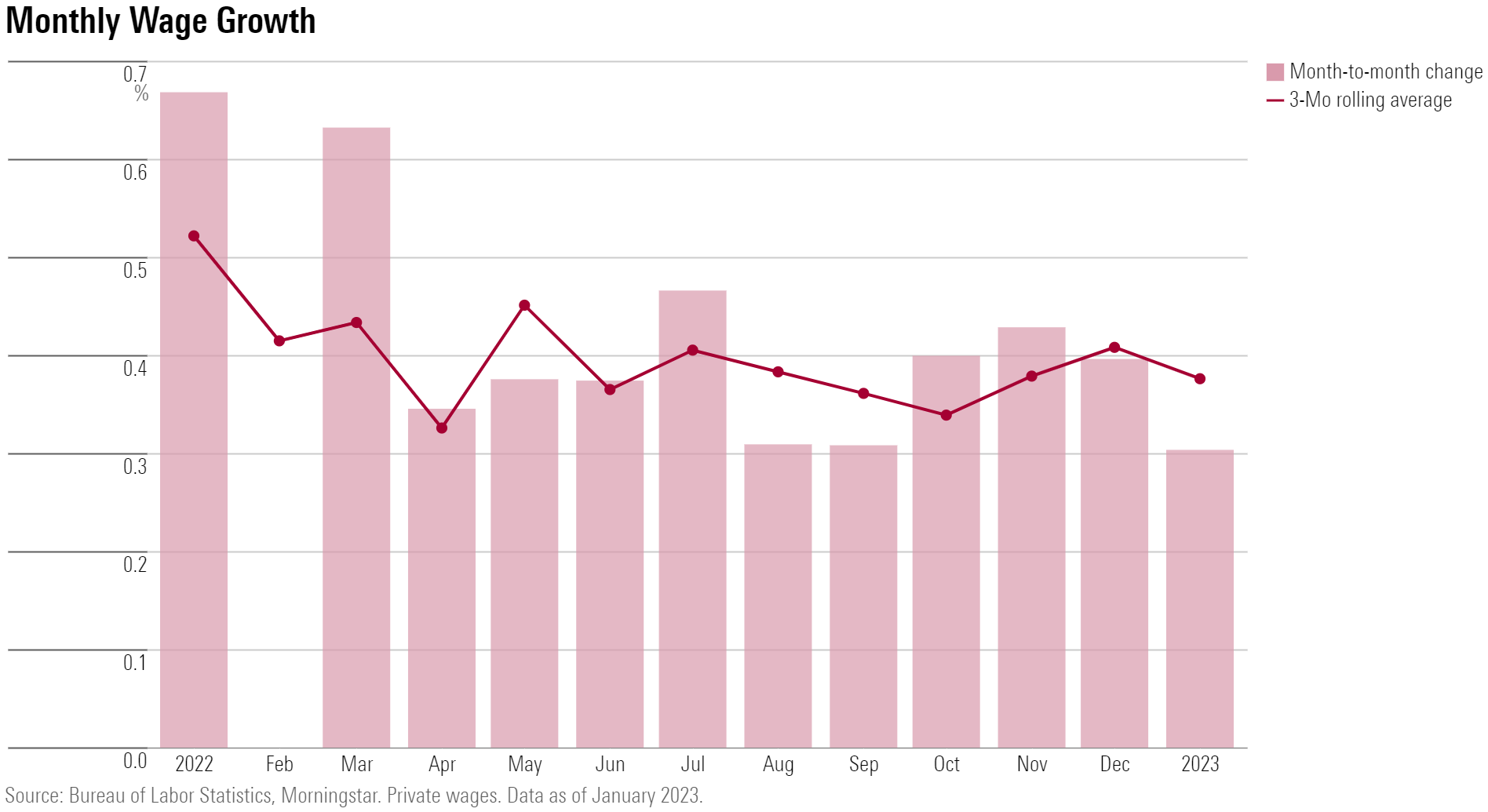

In one positive sign for Powell, wages rose 0.3 percent in January, down from 0.4 percent in December. What the Fed chair fears most is a “wage-price spiral” in which higher wages drive prices and create a dangerous inflation cycle. That is not evident in this report.

There is also a chance that seasonal factors, which often make January jobs figures hard to read, helped trigger the surprising number.

“The blowout 517,000 increase in total employment was almost certainly a function of seasonal noise and traditional churn in early year job and wage environment and exaggerates what is already a robust trend in hiring,“ Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at consulting firm RSM US, said in a client note.

The survey week that produces the jobs number was also unusually warm, something that could have boosted the total, said Ian Shepherdson, chief U.S. economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. “My guess is February will be back down around 200,000 because the trend is still slower.”

Economist Larry Summers — The former Treasury secretary under former President Bill Clinton has long been saying that more Fed rate hikes will be needed to rein in the labor market. This report could offer more fodder for that argument.

He said Friday that it was a positive report but struck a note of caution.

“No question this was a good number,” Summers said in an interview. “I think the question on inflation is whether getting through the final few miles will be nearly as cheap as the first few miles. We are still at levels that would have been deeply alarming two years ago.”

Summers was among the few who predicted fairly early that inflation would soar and stay high for a long period of time. At the time of his initial call last February, the Fed, the White House, and other Democrats were still assuring Americans that the inflation spike would be “transitory.” It wasn’t.

Summers has also repeatedly irritated the White House by suggesting that the trillions in new spending approved by Democrats in Congress and signed into law by Biden over the last two years played a role in the inflation spike.

He also maintained for months that the Fed’s rate-hiking campaign, while necessary, would almost certainly lead to significant recession and a near doubling in the unemployment rate. He has more recently softened his tone and been more receptive to the idea that a soft landing is even possible.

“I’m still cautious, but with a little bit more hope than I had before,” Summers said last month. “Soft landings are the triumph of hope over experience, but sometimes hope does triumph over experience.” This number is likely to get Summers to tilt back toward experience.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — The stunning jobs report will undercut the argument by McCarthy and other Republicans that Biden’s economy is fading fast under the weight of inflation, which they say is driven by big spending bills.

Still, the more aggressive the Fed feels it has to be in killing inflation, the higher the risk that the central bank will push the economy into recession. A slumping economy would give the Republicans ammunition to use against Biden and the Democrats in the 2024 campaign.

The January jobs report showed the opposite of what many investors and economists had expected: Instead of an economy heading toward a recession, the job market carried on at a confoundingly strong pace.

Despite mounting technology company layoffs and other signs of weakening in interest-rate-sensitive portions of the economy, strong job growth could mean the Federal Reserve will continue raising interest rates and hold them at higher levels longer, rather than the pause that markets had been increasingly expecting. In recent weeks, those hopes have led both stocks and bonds too strong rallies.

Payroll numbers for January showed the economy adding 517,000 new jobs, an increase that was well above economists’ forecasts. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate clocked in at its lowest level in over 50 years. Wages rose slightly, hand in hand with a growing labor supply that cooled any wage pressures. The month’s report came with revisions to the past two years’ data, adding to the complicated, surprising picture.

“If job growth is indeed as strong as the latest data suggests, then it presents a puzzle in light of other data showing a slowdown in economic activity, as well as widespread expectations of slow growth—and perhaps even a recession—in 2023,” says Morningstar’s chief economist Preston Caldwell.

Caldwell says that either job growth is being overestimated, economic growth is being underestimated, businesses are hiring aggressively into an imminent economic slowdown or a mix of all three. “And if businesses really are hiring aggressively ahead of an economic slowdown, then business profits are about to take a nosedive, which will likely lead eventually to reduced hiring and layoffs,” he says.

“Today’s report should incrementally push the Fed to a tighter monetary policy stance,” says Caldwell.

January Jobs Report Key Stats

- Total nonfarm payrolls rose by 517,000 versus 260,000 in December.

- The unemployment rate edged down to 3.4% from 3.5% in December.

- Average hourly wages grew by 0.3% to $33.03 after rising 0.4% in December.

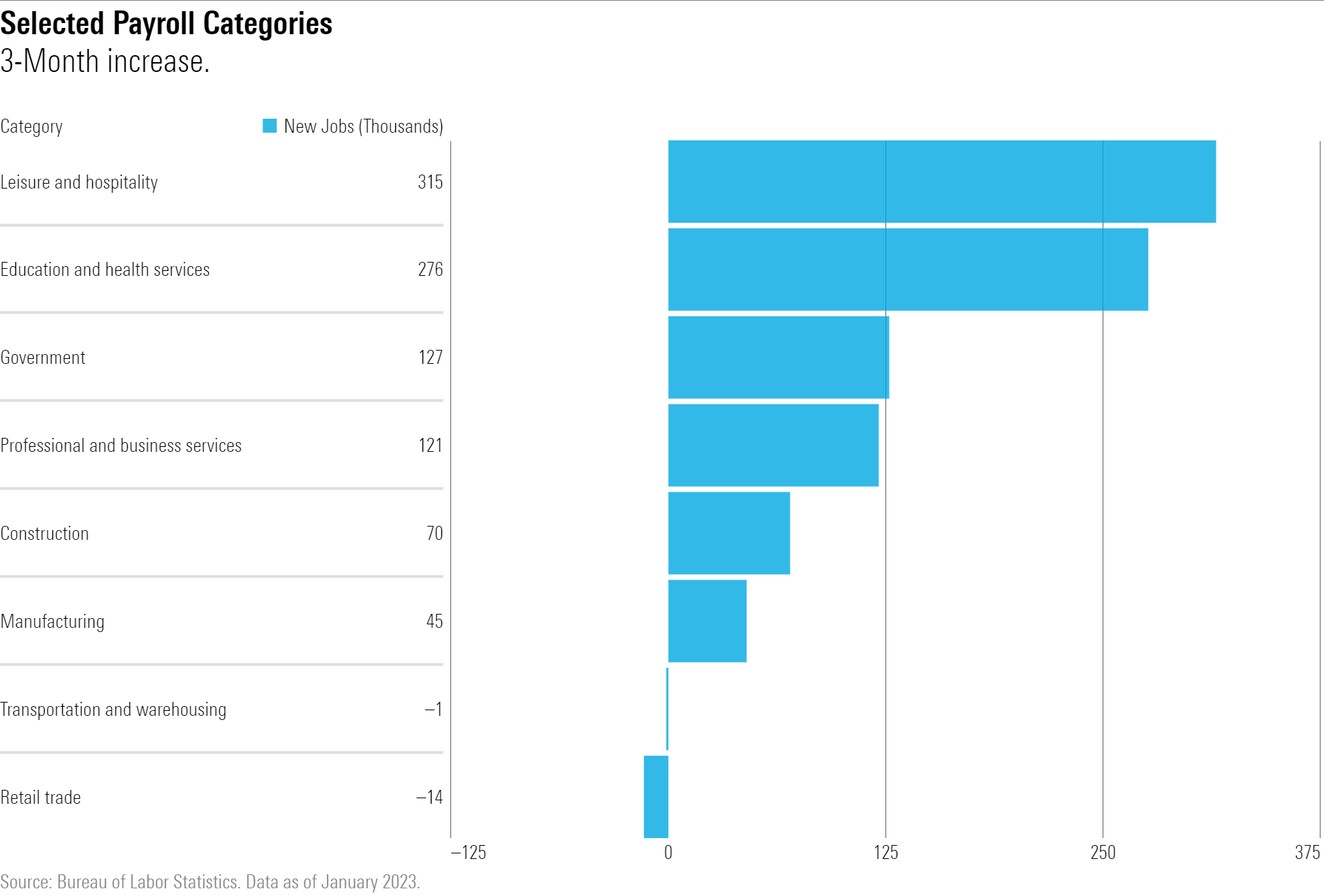

- Jobs in leisure and hospitality grew by 128,000 but remain below their pre pandemic February 2020 levels.

Jobs Growth Surges

The January jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed total nonfarm payrolls rose by 517,000, well above the average monthly gain of 401,000 in 2022, and much higher than consensus expectations from FactSet for January jobs growth of roughly 190,000.

Gains in hiring came across the board, led by leisure and hospitality, professional and business services, and healthcare.

For the three-month moving average, payrolls have grown at a 2.8% annualized rate. “That rate of job growth is more consistent with an economic boom than an incipient recession,” Caldwell says. “We can still detect a deceleration in job growth over the past year, but it’s been very gradual.”

Unemployment Rate Lowest Since 1969

The unemployment rate ticked down to 3.4% from 3.5% in December. The unemployment rate has held relatively steady over the past year. From March 2022 through December, the rate ranged between 3.5% and 3.7%.

But with the January decline to 3.4%, the unemployment rate slipped to its lowest level since 1969.

Within the jobs report, leisure and hospitality jobs rose 128,000 in January, above the average of 89,000 jobs per month in 2022. Employment in leisure and hospitality is still 2.9% below its pre pandemic February 2020 level. Continued strong growth in service-sector employment is a potentially worrying point for the Fed, economists say, as a tight labor market in those industries may be more prone to seeing wage inflation that would spill over into the broader economy.

Construction employment increased by 25,000 jobs in January, led by job gains for specialty trade contractors. Economists have been surprised by continued strength in construction hiring given the growing weakness in real estate resulting from the Fed’s interest-rate increases.

Jobs Report Shows Moderate Wage Growth

“The job growth data does point to a much stronger economy than anticipated, but in terms of wages, the economy isn’t looking overheated,” Caldwell says.

In January, average hourly wages rose by 0.3% to $33.03. Wage growth has averaged a 4.6% annual rate in the last three months, according to Caldwell. He says that number is slightly above normal levels, but still consistent with inflation at a relatively mild 3% long-term rise in prices.

“Despite proclamations of a ‘labor shortage’, labor supply is expanding almost hand-in-hand with business’ hiring needs,” Caldwell says. That means that businesses aren’t as pressured by a need to entice people into the workforce by raising wages. Moreover, he says, “Further slowdown in labor demand and job growth in 2023 should ease wage growth further.”

Jobs Report Shifts Outlook for Fed Rate Hikes

For investors, who increasingly have been looking for the Fed to halt its interest-rate increases by the end of the year, the strong jobs data throws a wrench into that outlook.

“There was a good possibility of a pause in rate hikes, but now it’s much more likely that the Fed will hike again,” Caldwell says.

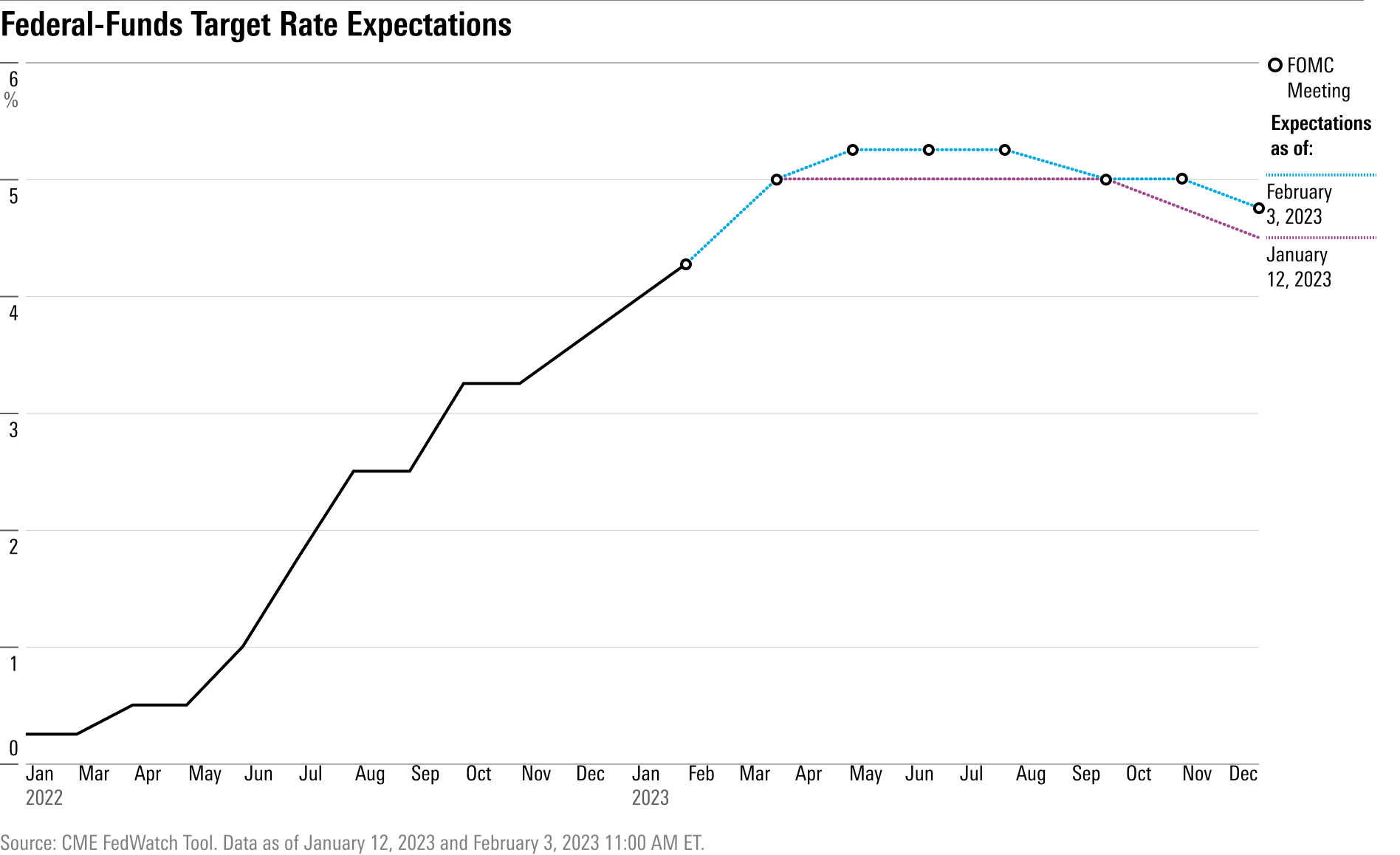

After the report’s release, market expectations held steady for a 0.25-percentage-point increase in the federal funds rate at the March Fed meeting. According to the CME FedWatch Tool, a quarter-point increase in the fund's rate target to 4.75-5.00 is given a 97% likelihood, up from 83% before the report’s release.

But further out, the jobs data prompted a shift in expectations for the Fed raising rates higher and holding them in place longer.

For the May meeting, odds are now seen in favor of another quarter-point increase, which would take the funds rate to a target rate of 5%-5.25%. And while bond futures suggest the Fed is expected to lower rates by the end of 2023, those cuts are now pushed back to the fourth quarter. The majority of market participants expect the fed-funds rate to land at 4.75%; a month ago, most expected the rate to fall to 4.50% by December.

“Exceedingly Strong” Jobs Market in 2021 and 2022

The January jobs report released also showed large upward revisions to historical data on nonfarm payroll growth for 2021 and 2022.

“Altogether, this paints a picture of a post-pandemic jobs recovery that has been exceedingly strong, with January 2023 nonfarm employment at 2% above pre pandemic levels,” Caldwell says.

These revisions were part of the regular annual updates, where the U.S. Department of Labor supplements the original reporting with higher-quality data from unemployment insurance records and recalibrates its historical estimates.

The new data shows December nonfarm payroll employment was 800,000 higher than previously reported.

However, Caldwell says investors shouldn’t extrapolate those historical revisions going forward. “It’s quite possible that next year’s benchmark revisions will show job growth in late 2022 and early 2023 was much weaker than currently reported,” he says. “One plausible reason is elevated levels of a business closure.” The BLS uses a statistical model to estimate rates of business openings and closures, which is liable to be wrong at key turning points in the business cycle, he says.

Caldwell notes that while these data issues may seem arcane, they are important to keep in mind as we evaluate the job data. “If the Fed is evaluating the economy using flawed data, it may set monetary policy at inappropriate levels. In many recessions—including 2008—both gross domestic product and employment ended up later being revised downward.” Caldwell says that Fed is aware of this tendency, which is why it uses a diverse array of data to evaluate the state of the economy rather than relying on a single report.

Does the Federal Reserve have it wrong?

For months, the Fed has been warily watching the U.S. economy’s robust job gains out of concern that employers, desperate to hire, would keep boosting pay and, in turn, keep inflation high. But January’s blowout job growth coincided with an actual slowdown in wage growth. And it followed an easing of numerous inflation measures in recent months.

The past year’s consistently robust hiring gains have defied the fastest increase in the Fed’s benchmark interest rate in four decades — an aggressive effort by the central bank to cool hiring, economic growth, and the spiking prices that have bedeviled American households for nearly two years.

Yet economists were astonished when the government reported Friday that employers added an explosive 517,000 jobs last month and that the unemployment rate sank to a new 53-year low of 3.4%.

“Today’s jobs report is almost too good to be true,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter. “Like $20 bills on the sidewalk and free lunches, falling inflation paired with falling unemployment is the stuff of economics fiction.”

In economic models used by the Fed and most mainstream economists, a job market with strong hiring and a low unemployment rate typically fuel higher inflation. Under this scenario, companies feel compelled to keep boosting wages to attract and keep workers. They often then pass those higher labor costs on to their customers by raising prices. Their higher-paid workers also have more money to spend. Both trends can feed inflation pressures.

Yet even as hiring has been solid in the past six months, year-over-year inflation has slowed from a peak of 9.1% in June to 6.5% in December. Much of that decline reflects cheaper gas. But even excluding volatile food and energy costs, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge has risen at about a 3% annual rate over the past three months — not so far above its 2% target.

Those trends have raised questions about a core aspect of the Fed’s higher rate policy. Chair Jerome Powell has said that conquering inflation would require “some pain.” And the Fed’s policymakers have forecast that the unemployment rate would rise to 4.6% by the end of this year. In the past, an increase that large in the jobless rate has occurred only during recessions.

Yet Friday’s report suggests the possibility that the long-standing connection between a vigorous job market and high inflation has broken down. And that breakdown holds out a tantalizing possibility: That inflation could continue to decline even while employers keep adding jobs.

“Their model is that this inflation is driven specifically by wage inflation,” said Preston Mui, senior economist at Employ America, an advocacy group. “In order to get that down, they think we have to bring some pain in the labor market in terms of higher unemployment. And what the past three months have shown us is that that model is just wrong.”

That said, it’s possible that Friday’s report could still nudge the Fed in the opposite direction: The consistently strong job growth might convince Powell and other officials that, despite signs that wage growth is slowing, a powerful job market will inevitably reignite inflation. If so, their benchmark rate would have to stay high to cool the pace of hiring.

With that outlook in mind, Wall Street traders are now pricing in an additional Fed rate hike this year: Investors foresee a 52% likelihood that the Fed will raise its benchmark rate by a quarter-point in both March and May, to a range of 5% to 5.25%. That’s the same level that Fed officials themselves had predicted in December.

Many economists say the pandemic so disrupted the job market that it is acting differently than it has in the past.

“There are a lot of norms .... that aren’t normal anymore,” Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said Friday. “We’re seeing a lot of companies maybe not doing layoffs in January that they normally would have because they went through a pandemic where they lost people and they didn’t come back.”

At a news conference this week, Powell argued that much of the easing in inflation since the fall has reflected falling prices for goods — items like used cars, furniture, and shoes — as well as sharply lower gas prices. Those price declines reflect a clearing of formerly clogged supply chains, he suggested, and will likely prove temporary.

And Powell reiterated one of his central concerns: That inflation in the labor-intensive services sector is still rising at a steady 4% pace and shows no sign of slowing. Much of that increase is a consequence of strong wage growth at restaurants, hotels, and transportation and warehousing companies, with fewer workers available to take such jobs.

“My own view,” the Fed chair said, “would be that you’re not going to have a sustainable return to 2% inflation in that sector without a better balance in the labor market.”

Yet even with the vigorous job gains, several measures of wage growth show a steady easing: Average hourly pay grew 4.4% in January from a year earlier, down from a peak of 5.6% in March.

“More focus should be placed on the earnings data,” said Rob Clarry, investment strategist at Evelyn Partners, in a research note. “The high headline (job) reading does not appear to be translating into further inflationary pressure — an important finding for the Fed.”