U.S. consumer prices did not rise in July due to a sharp drop in the cost of gasoline, delivering the first notable sign of relief for Americans who have watched inflation climb over the past two years.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) was unchanged last month after advancing 1.3% in June, the Labor Department said on Wednesday in a closely watched report that nevertheless showed underlying inflation pressures remain elevated as the Federal Reserve mulls whether to embrace another super-sized interest rate hike in September.

Economists polled by Reuters had forecast a 0.2% rise in monthly CPI in July on the heels of a roughly 20% drop in the cost of gasoline. Prices at the pump spiked in the first half of this year due to the war in Ukraine, hitting a record-high average of more than $5 per gallon in mid-June, according to motorist advocacy group AAA.

But the Fed has indicated that several monthly declines in CPI growth will be needed before it lets up on the increasingly aggressive monetary policy tightening it has delivered to tame inflation currently running at four-decade highs.

U.S. consumer prices have been surging due to a number of factors, including snarled global supply chains, massive government stimulus early in the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Food is one component of the CPI that remained elevated in July, rising 1.1% last month after climbing 1.0% in June.

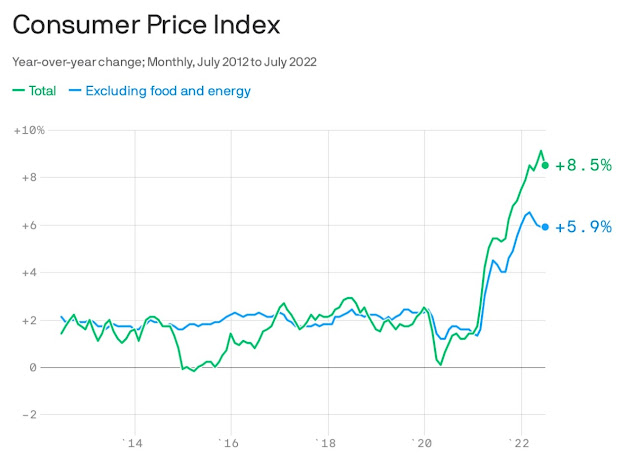

In the 12 months through July, the CPI increased by a weaker-than-expected 8.5% following a 9.1% rise in June. Underlying inflation pressures, which exclude volatile food and energy components, also showed some encouraging signs.

The so-called core CPI rose 0.3% in July after climbing 0.7% in June, but increased 5.9% in the 12 months through July, the same pace as in June.

Inflation in the cost of rent and owners' equivalent rent of primary residence, which is what a homeowner would receive from renting a home, held almost steady last month. Shelter costs comprise about 40% of the core CPI measure.

Consumer Price Index inflation cooled meaningfully in July as gas prices declined, which is good news for the Federal Reserve, though not yet enough for policymakers to conclude that America is through the worst of its burst of rapid price increases.

While costs finally stopped increasing at an accelerating rate, they are still climbing at an unusually rapid clip, making everyday life expensive for consumers. And a big chunk of the pullback in July came from dropping gas prices, as the average cost of a gallon of fuel began to fall back toward $4 after peaking at $5 in June.

Fuel costs are notoriously volatile, and with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine injecting heightened geopolitical tensions, officials are unlikely to stake victory on a slowdown that could quickly reverse itself. That said, the report contained other good news: Airfares came down in price, which was expected, but so did the cost of apparel, hotel rooms used cars. The slowdown in core prices, which strip out volatile food and fuel costs to give a sense of the underlying trend, was more pronounced than economists had expected.

Despite all those positive developments, costs continue to climb rapidly across many goods and services. Rapidly rising rents are likely to particularly stick out to the Fed because they make up a big chunk of overall inflation.

The big question on Wall Street is what the new data will mean for the Fed’s policy path ahead — and investors on Wednesday interpreted the fresh data as likely to allow the central bank to slow down its rapid rate increases.

The Fed raised interest rates by three-quarters of a percentage point in both June and July, and officials have signaled that another one of those abnormally large increases should be up for debate at their upcoming meeting on Sept. 20-21. But investors are betting that slower inflation and moderating inflation expectations could shore up support for a smaller move.

Still, Fed officials have warned against reacting too much to one data point.

“It can’t just be one month. Oil prices went down in July; that’ll feed through to the July inflation report, but there’s a lot of risks that oil prices will go up in the fall,” Loretta Mester, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, said during a recent appearance. It would be a mistake to “cry victory too early.”