Over the past 60 years, the type of work Americans do has undergone a dramatic shift. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, nearly a third of people worked in manufacturing — building the cars, airplanes, washing machines, and televisions that their neighbors used and that defined America. Nowadays, more than 80% of Americans work in a service industry, from finance and nursing to restaurants and baggage handling. Less than 10% are in manufacturing.

For some economists and policymakers, this shift was inevitable; as better technology made factories more efficient, companies could move production to countries where workers' pay was lower. They argue that the shift was as natural as the US moving from farming to manufacturing over a century ago and that efforts to revitalize manufacturing in the US are a lost cause.

But this shift from a more balanced economy to one disproportionately dependent on services used by wealthy elites has had other effects — namely the shrinking of the middle class and the explosion of economic inequality. Research indicates that the flight of factory jobs from urban cores has contributed to chronic poverty among Black families. And MIT economist David Autor has found that job losses associated with expanded trade with China didn't just result in manufacturing job losses — but also led to lower incomes and greater welfare dependency for the entire surrounding communities, especially smaller cities and towns in the Midwest.

Efforts to close these gaps have focused on the need to improve the quality of jobs in the service sector, such as caregiving and retail, were mostly women and people of color work. But what if we're resigning the US to a service-only economy too soon? What if we can create good-paying jobs producing the stuff we need? There are clear signs that manufacturing can make a historic comeback — helping rebalance the economy and give opportunities to the individuals and communities who were most hurt by the decline of the American factory in the first place.

Why it's important to have a manufacturing comeback

If a fairer economy is the goal, rebuilding the manufacturing sector is worth the effort. In 2020, manufacturing jobs paid, on average, $73,000 a year, far more than jobs in some of the largest service industries, such as retail ($36,759), leisure, and hospitality ($25,874), and education and health services ($55,355). For workers with similar education and experience, manufacturing jobs paid about 10% more than other occupations in the 2010s.

Still, the overall compensation advantage (including benefits) of manufacturing jobs has declined from roughly 17% in the 1980s to 13% in the past decade as the percentage of manufacturing jobs covered by a union has fallen by about half, to 8.5% in 2021 from 15.5% in 2001. Moreover, manufacturers have turned to temporary-help agencies and other outsourcing strategies to retain frontline workers instead of paying those workers more, which in turn has lowered pay at the bottom rungs of the sector.

Manufacturing jobs are particularly important to rural communities. In small towns in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota in 2017, one in every four private-sector jobs was a manufacturing job — a much higher percentage than in cities in those states. A strong manufacturing sector can level the playing field between cities and small towns that have seen their jobs shipped overseas and factories fall into decay. By making jobs more available throughout the country, in suburban and rural areas alike, we can ease some of the migration rushes to cities and lower the excruciating cost of living in large metros.

A strong manufacturing sector benefits all of us. Manufacturing towns that have retained more factory jobs are more likely to see higher employment gains in the service sector since factory workers need school and hospital employees in their communities. America's technological edge is strengthened with a robust manufacturing sector providing well-paying jobs. Boosting US manufacturing would also reduce the trade deficit with China and other nations, growing national income and raising the standard of living for Americans.

Now is the time for the great American manufacturing comeback

Some people will say: Sure, having more manufacturing jobs would be great, but if the industry has been slipping for decades, why is now the time for a comeback?

For one thing, the American people increasingly want it. The COVID-19 pandemic — and our continuing struggles to contain supply-chain-driven inflation — has made Americans more attuned to the importance of manufacturing to our economy and clearly demonstrated what happens when we rely too heavily on foreign production. Without sufficient capacity at home to quickly manufacture personal protective equipment, we had to obtain it from overseas — but inspectors discovered that 60% of imported masks did not meet US standards. For months, car production stalled because of a global shortage of semiconductors, which led to massive price hikes, especially for used cars. That might not have been a major problem for us 20 years ago when 37% of semiconductors were produced in the US — but today, only 12% are.

A recent survey by Deloitte suggests Americans increasingly have a positive view of manufacturing, with roughly three in four respondents saying the sector was critical during the pandemic. That is translating to growing bipartisan support for ideas such as investing in US computer-chip manufacturing and a greater willingness among talented young people to entertain manufacturing careers.

What's more, the sector is positioned for a resurgence, if only it could get a bit of help. Increased demand for goods in the pandemic has led manufacturing to rebound faster than the economy as a whole, recovering 96% of the jobs lost at the onset of the pandemic. The Reshoring Initiative estimated in 2021 that about 220,000 manufacturing jobs would return to the US, describing it as by far the highest annual number it had recorded. Manufacturing jobs have grown in 92 of the past 120 months; in the decade prior, the sector shrank in 85 of 120 months. After dropping off precipitously in 2020, real US manufacturing output soared to $2.8 trillion in the first quarter of 2022 as the economy roared back.

What's holding manufacturing back and what can unleash it

Manufacturing's revitalization has been stymied by two main factors: a lack of a new workforce and a lack of investment. Both issues can be solved, but only if the industry and lawmakers work to reverse some of the conditions that crushed America's producers, to begin with.

For one, manufacturing's homogenous workforce is dying off (or at least retiring. The sector had a record 943,000 open jobs last July, and the number had ticked down to only 809,000 in May. That was more than double the number of unfilled positions from before the pandemic, while the economy overall had about 60% more openings. And the job crisis is expected to get worse. A study from 2015 projected that over the next decade, nearly 2 million desperately needed manufacturing jobs would go unfilled. In field research for the Century Foundation, I've visited factory floors in which the entire production and skilled-trades workforce was over 60. The need for workers is too large for manufacturers to rely on their usual "FBI" method of recruitment, sourcing new employees from the friends, brothers, and in-laws of their current workforce.

Manufacturing has always been an overwhelmingly white and male occupation, but if anything the lack of diversity has worsened in recent decades. The number of Black workers in the sector dropped by 30% from 1998 to 2020, a loss of 604,500 lost jobs. Women have also consistently lagged in their representation in the manufacturing sector. And in a 2016 report, the Institute for Women's Policy Research found that women held only 7% of good-paying manufacturing jobs that require a high school diploma but no college degree. Among so-called middle-skill jobs like these, only the construction sector has a lower percentage of women workers. It's not uncommon to visit a factory that doesn't even have a women's bathroom, to say nothing of the rampant sexual harassment that women in manufacturing jobs experience. And even when women and Black and Hispanic workers do enter the workforce, their upward mobility is limited. White manufacturing workers are three times as likely to be in management positions as workers of color. Diversifying the manufacturing workforce will be key to the sector's success.

A generation ago, 80% of manufacturing workers had only a high-school diploma or less; in 2016, a greater share of workers had a postsecondary credential, such as a two-year degree, industry certification, or apprenticeship. Many companies have begun to realize this, launching partnerships with labor unions and educational institutions — especially community colleges and high schools — to establish apprenticeships and shorter-term programs to provide the skills people need to thrive in a manufacturing career. But to be effective, such programs should prioritize connecting new recruits to women and people of color in the industry who can mentor them.

The other big challenge facing manufacturing is turning American-made innovations into American-made products. Whether it's automation or biotechnology, the future of manufacturing is high-tech. But while Silicon Valley and our universities remain global leaders in technological research, too often the product of the resulting products occurs overseas. In the US, only a sliver of venture-capital investments goes to hard technologies like manufacturing.

States like Missouri, Indiana, and Ohio have established state-supported venture-capital development funds to invest more in manufacturing startups in the heartland. The federal government should match these efforts and make sure products from lithium batteries to biopharmaceuticals are produced here at home.

The tech investment we do have does not reach all parts of the country equally. To address this, Congress has proposed — and should enact — a program that would establish so-called regional technology hubs to direct federal investment in advanced manufacturing technologies to communities that have not had such investment.

Manufacturing can help rebuild the middle class

Manufacturing was once the engine of America's economic might. As our economy rebuilds from a pandemic that laid bare just how important the sector is to our collective health and well-being, manufacturing can once again provide much-needed, high-quality, good-paying jobs to those who need them most. In fact, the signs of a manufacturing renaissance are already here.

The wave of people leaving their jobs over the past few years is showing no signs of slowing down, and for many willingly choosing to quit, a massive reinvention of their ideal career is underway.

The number of employees who are considering quitting their jobs right now is around 40%, a number that hasn’t changed much in recent months.

A survey by Microsoft in March found that 41% of workers were thinking about leaving their jobs, and another survey last week by McKinsey put that number at 40%.

“This isn’t just a passing trend, or a pandemic-related change to the labor market,” Bonnie Dowling, a co-author of the McKinsey report, told CNBC. “There’s been a fundamental shift in workers’ mentality, and their willingness to prioritize other things in their life beyond whatever job they hold.”

But while the number of workers who want to leave their jobs has remained remarkably consistent, fewer and fewer are reverting to traditional office jobs, with a growing number seeking nontraditional roles, or even the opportunity to start a new business.

‘The Great Rethink’

Since 2021, records have been racking up for workers prepared to voluntarily leave their jobs.

It’s been dubbed the Great Resignation, and with 4.3 million people quitting their jobs in May, the number of resignations is still virtually unchanged from last year.

At first, resignations were being fueled by workers desiring higher pay, better benefits, and more fulfilling work. Those same factors are still around right now, but with an added ingredient thrown into the mix: inflation.

With prices in the U.S. running at a 40-year high, snail-paced wage raises, and a near-record high number of job openings, why wouldn’t workers be looking for greener pastures?

But after years of pandemic-era living, those new pastures are more diverse than ever, and many resigning workers are deciding to take much more adventurous steps.

As many as 18% of U.S. workers who quit their job are returning to work in nontraditional roles, according to the McKinsey report, including part-time jobs, temporary gigs, or even starting their own business.

Many workers who quit their job also do so to shift towards a different industry, according to the report, even if it means departing from a highly lucrative field.

Of people in the past year who quit jobs in finance and insurance areas, 65% did not return to the workforce or departed for a different job sector, as McKinsey’s Dowling told Fortune’s Sheryl Estrada this week.

The desire for more flexibility has been one of the main sticking points of the Great Resignation, as the pandemic popularized employee habits like remote work and working independent hours outside of a traditional 9-to-5.

The desire to work nontraditional hours, or to set one’s own hours, is part of how many workers are completely reevaluating their relationship with work.

“A better description of this phenomenon would be a ‘Great Rethink’ in which we are all rethinking our relationship to work and how it fits into our lives,” Ranjay Gulati, professor of business administration at Harvard University and author of the 2022 book Deep Purpose: The Heart and Soul of High-Performance Companies, recently wrote for Fortune.

But while more people than ever are feeling ready to change industries or work in a more nontraditional setting, the sheer volume of quitting means that not everyone who resigns ends up satisfied.

A recent report by Joblist, analyzing data from June, found that 26% of people who quit their jobs regretted their decision, and 42% of respondents who had returned to the workforce said that their new position had failed to live up to their expectations.

The United States is perilously close to falling into a recession, despite the reassurances of Federal Reserve officials, Wall Street economists, and financial journalists. That’s not just an idle opinion; it’s what the data say.

Let’s let the numbers speak for themselves.

‘A deep, widespread, and lasting downturn’

Contrary to what you’ve heard, a recession — at least in the U.S. — is not defined by two straight quarters of falling gross domestic product (GDP). It’s more nuanced than that.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, a private body that’s been accepted as the official historian of U.S. business cycles, “a recession involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” The key elements are depth, diffusion, and duration.

The decline in GDP in the first quarter would not meet the criteria, because the weakness was not widespread; it was confined to one part of the economy — the trade deficit — while the rest of the economy grew at a healthy rate. Indeed, imports were high precisely because domestic demand was strong.

And an expected decline in the just-concluded second quarter — we’ll find out next week when the data are released — might not meet the diffusion criteria either, because most of the apparent weakness was in home building and inventory growth, not in consumer spending or business output.

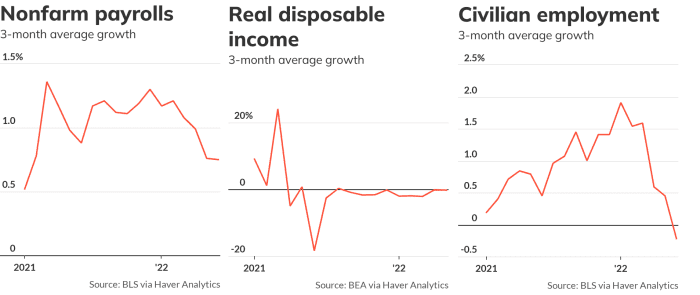

In practice, the NBER looks primarily at six monthly coincident indicators to judge whether the economy is expanding or contracting and whether a slump meets the test of depth, diffusion, and duration.

The U.S. has never endured a recession without a significant decline in jobs and a concurrent rise in unemployment. But Japan has.

The most important number is the growth of nonfarm payrolls, collected in a survey of businesses. Not only is employment inherently the most important gauge of the health of the economy, but the payroll survey is considered to be the most statistically reliable of all the coincident indicators.

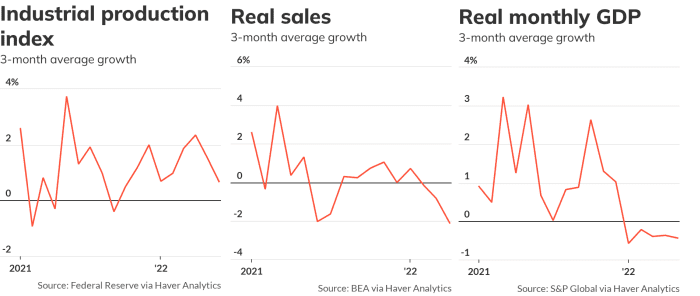

Other factors are also considered, such as the growth of real personal incomes, industrial output, and real sales by businesses. (“Real” means adjusted for inflation.)

These four indicators — payrolls, incomes, output, and sales — comprise the index of coincident indicators, which is released by the private Conference Board each month. The coincident index rose 0.2% in June, the group reported Thursday.

The NBER also looks at a monthly estimate of GDP, and an alternate view of civilian employment obtained from a survey of households. It also takes quarterly gross domestic product and gross domestic income into account. NBER does not use the unemployment rate, because it’s actually a lagging indicator.

The coincident indicators

Four of these six coincident indicators — real disposable incomes, real sales, civilian employment, and monthly GDP — have declined over the past three months. (Caveat: I’m using a slightly different measure of income than the NBER has traditionally used because the traditional measure is sending a misleading signal right now. But incomes are slowing quite a bit by either measure.)

A fifth indicator — industrial output of factories, mines, and utilities — has been slowing and actually fell in the latest month.

Of the six indicators, only nonfarm payrolls have continued to grow at a decent rate. Is that enough to give us confidence that the economy is not in a recession? Typically, the answer would be “yes.” That’s why Fed Gov. Christopher Waller was so certain when he said recently that “it would be tough to say we have a recession with 3.6% unemployment.”

The U.S. has never endured a recession without a significant decline in jobs and a concurrent rise in unemployment. But Japan has.

In Japan, the economy can slip into recession without increasing unemployment because Japanese companies tend to retain employees even when their revenue drops sharply. Japan is an aging society, and workers are so scarce that companies will keep them on the payroll (at reduced pay and hours) through a slump until the economy recovers.

That sounds a lot like the current dynamic in the U.S. economy, with companies facing a shortage of able and willing workers. (And it’s becoming a structural problem for the U.S. as it is for Japan.) It’s possible that the U.S. economy will start behaving more like Japan’s now that its demographics look more like Japan’s.

Universally bleak

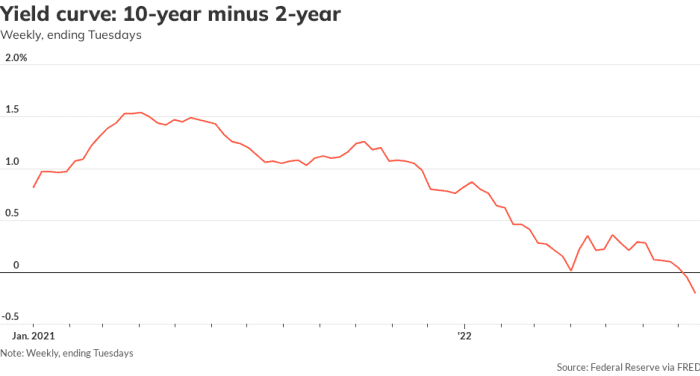

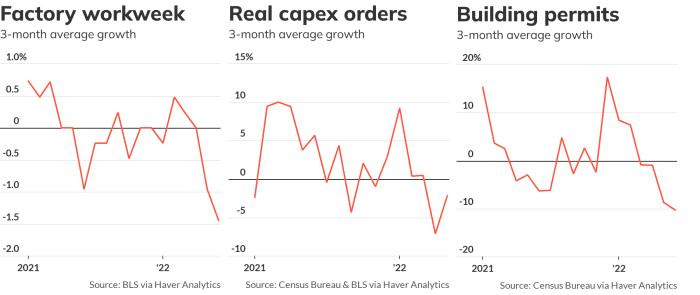

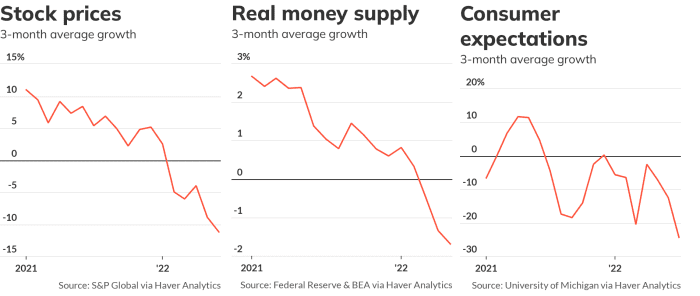

Aside from these six indicators that tell us how the economy is faring now, economists have identified other economic data that hint at what the economy will look like in the near future. These so-called leading indicators are universally bleak.

On Thursday, the Conference Board said that “U.S. recession around the end of this year and early next is now likely” after it reported that the index of leading indicators fell 0.8% in June.

The granddaddy of leading indicators is the yield curve, which is determined by the spread between the yield on the 2-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD02Y,

The other leading indicators

The other major leading indicators were already negative. The money supply is falling now that the Fed is tightening up on credit and shrinking its balance sheet.

Building permits — which point to future construction — are collapsing as the Fed pushes up interest rates and makes homes even more unaffordable. Consumer expectations have sunk as inflation batters household budgets.

Businesses are losing confidence as well. With consumers retrenching, businesses have cut back on investments in capital goods, and factories are cutting workers’ hours. Stock prices SPX,

The risk is high

I don’t have a crystal ball. I don’t forecast the economy. I don’t know if the U.S. is fated to fall into a recession, or if it’s already in one. Perhaps the bulls are correct that inflation will moderate just enough to give consumers and businesses confidence and income to keep the expansion going.

But I do worry that policymakers, economists, investors, and journalists may be too nonchalant about the risk of a recession this year. The data suggest that the risk is high and rising.