The U.S. is now experiencing the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression—with the starkest levels of wealth inequality since the 1920s. We need to act, but how? Perhaps we should heed the significance of today, International Equal Pay Day, to guide our path forward.

Grounded in the data and the spirit of American resilience, I’m calling for a furthering of the social contract. We the People must unambiguously embrace stakeholder capitalism. Such an embrace would unleash sustainable economic growth for customers, employees, partners, communities, and society at large. This is America’s future.

To accomplish this next stage of capitalism, we must shake ourselves from the binds of a false narrative, the one that pits the interests of stakeholders against the interests of shareholders. This narrative has fueled, albeit inefficiently, American corporations on the taxpayer dime.

If we are serious about digging ourselves out of today’s economic turmoil and creating economic prosperity for all, then we must overhaul our current revenue-and-profits-based performance indicators used to evaluate the success of a corporation.

Traditional financial reporting took us this far. It’s time to pass the baton. To recalibrate our economy, we need to implement a new set of key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure and track organizational success.

Why stakeholder capitalism clashes with traditional financial reporting

2015 was the first year on record that the middle class no longer constituted the majority in the US. Now, the top 1% of U.S. families hold more wealth (over $25 trillion) than the entire American middle class ($18 trillion).

That’s why Americans applauded in August 2019 when the Business Roundtable redefined the universal purpose of a company in pursuit of an economy that serves all stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders alike. In calling for a new standard of corporate responsibility, top CEOs from around the country recognized that “Americans deserve an economy that allows each person to succeed through hard work and creativity and to lead a life of meaning and dignity.”

Unfortunately, no matter how noble the intentions, businesses cannot and will not realize their newfound purpose until we expand the scope of standard reporting metrics.

Today’s shareholders evaluate company performance using standard metrics such as revenue, profit, return on capital, margin, share price, and capital efficiency. When a company performs well according to this set of metrics, investors show their support by buying that company’s stock. Existing shareholders are rewarded when stock prices rise and CEOs reap the benefits via compensation and professional accolade. Expecting CEOs to suddenly shift their focus away from the metrics that shareholders (and by proxy the board of directors) primarily care about goes against the status quo.

Lest we forget how budding enterprises are funded in the first place: Entrepreneurs succeed in growing their businesses by selling the promise of financial return to investors across the spectrum—angel investors, venture capitalists, retail investors, institutional investors, banks, and other financial institutions.

And yet, shareholder primacy is a myth we have already busted. In the long-term, what’s good for customers, employees, and the community is good for shareholders too. Companies with intersectionality gender-equitable workforces (i.e. with equitable rates of pay, promotion, and performance evaluation across gender, race, ethnicity, and age) increase their profitability, return on equity, innovation, productivity, and ability to attract top talent.

My company, Pipeline, conducted original research across 4,161 companies in 29 countries, subsequently collecting over 1 billion data points, and found that for every 10% increase in intersectional gender equity, businesses see a 1% to 2% increase in revenue.

Moreover, companies that support diverse, equitable, and inclusive (DEI) workforces not only perform better in good times, they also are better at weathering economic downturns. Between 2007 and 2009, the S&P 500 declined by 35%. However, businesses where key employee groups (such as women and people of color) said they had “very positive experiences” saw their stocks rise an average of 14.4%.

DEI businesses beating the market extends beyond the boundaries of a recession too. The stocks of DEI businesses where key employee groups thrived rose 35% between 2006 and 2014, whereas the aggregate S&P 500 only rose 9% during the same time.

How to overcome diversity data deficits

The basis for standard DEI reporting should stem from the current Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) requirements. As it stands, companies with 100 or more employees must provide data on gender and race broken down across 10 different job classifications every year.

From here, we must demand a series of updates. First, this data must be made public every year. Today, a mere 4% of companies voluntarily publish their data. Second, we must include pay data to the already-required reporting on gender and race across job classifications. Third, we must add a new category of metrics to track the entire employee lifecycle by gender, race, and ethnicity. These metrics include rates of promotion, representation on every step of the corporate ladder, representation on boards, performance evaluation scores, and access to resources, sponsorships, and growth opportunities.

Now is the time to move from self-reported data and optional reporting to a standard set of key performance indicators that are based on real data.

At best, the absence of DEI metrics will damper efforts to achieve the ideals of stakeholder capitalism. At worst, it will deepen the growing wealth inequality already undermining our economic prosperity and democracy—in which case everyone is held back. We could, for instance, expand the U.S. economy by $512 billion simply by closing the intersectional gender pay gap (though of course, that would not be simple).

Supporting the next iteration of the great American experiment

Most of the commitment to DEI has been outward-facing. We’ve seen press releases, such as this one by the Business Roundtable, against racial injustice. We’ve seen over $2.8 billion in donations pour in from large public companies to fight systemic racism. Black squares on social media.

But where’s the commitment to hire people equitably, to promote them equitably, and to pay them equitably? And where can we find the data to prove companies are making good on these commitments? How can we be certain that companies truly stand for DEI when five of the largest U.S. tech companies represent 22.7% of the S&P 500, and yet less than 3% of workers from the largest tech companies identify as Black?

For it’s part, the Business Roundtable has publicly committed to increasing minimum wages, investing in opportunities for employee growth, and expanding affordable access to healthcare. But where is the data to prove they pay their employees equitably? What about the data to prove they promote people at equitable rates? How will we know that they evaluate performance objectively and in an unbiased manner?

In the wake of COVID-19’s economic fallout and amid renewed calls for racial justice, we need to raise corporations to a higher calling. Because what’s good for employees, customers, and communities is also good for shareholders. Stakeholder capitalism expands the tax base, increases consumer spending (which drives 70% of the US economy), and brings us one giant step closer toward equity for all. It is the next iteration of American greatness.

How to Choose a 21st Century Career

How many times have you heard a sentence that started with the words “I wish I had…”? College graduates wish they had understood how the world works before they chose their majors (or, indeed, whether to attend university at all). Middle-aged men and women wish they had chosen this industry over that.

Everybody has 20/20 hindsight, but peering into the future is a completely different animal. For my young readers, there is no better use of your time than to try to understand two things:

- Which industries will blossom in the coming decades

- Which skills will be required within those industries

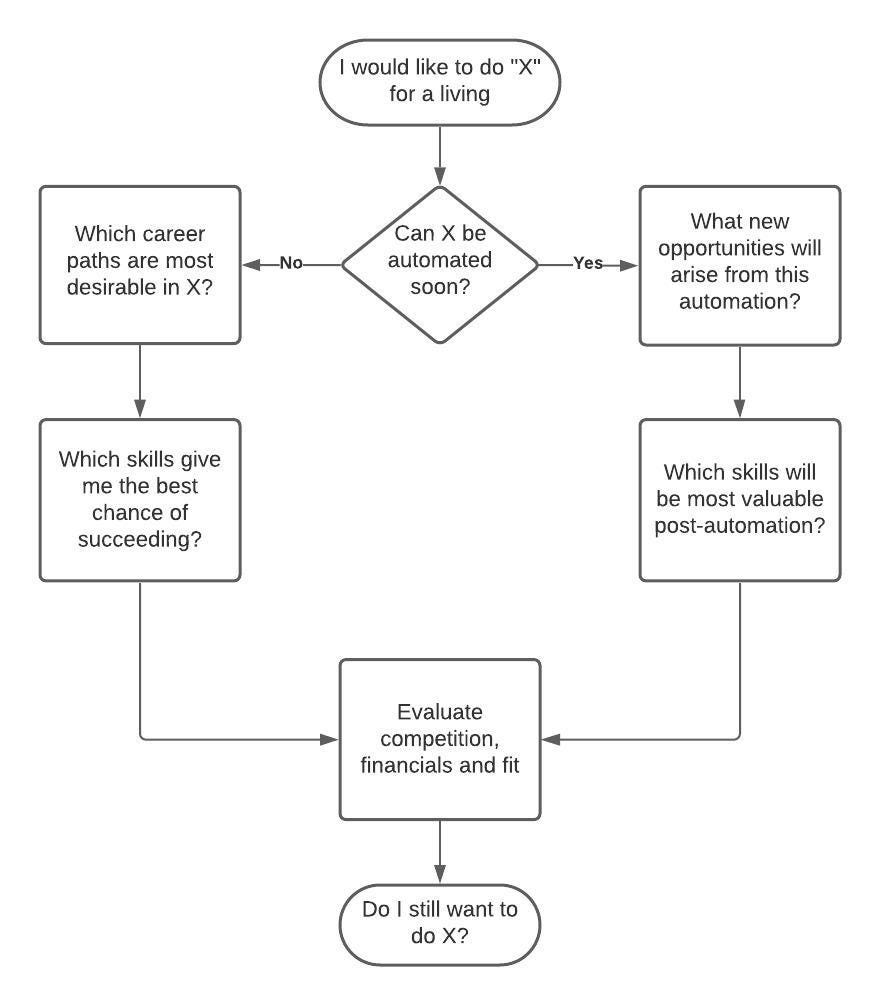

When trying to imagine the future today, the keyword is automation. You don’t want to be the guy training to drive a horse carriage the year before cars are invented. Once you start considering the implications of automation, your mind might swirl, and with good reason. But, is there an algorithm that can help us tackle this problem? The answer is yes.

For example, let’s say your first thought is: I want to build websites for a living. That’s great. Now, will web development be automated soon? It already has been, to a great extent. There are plenty of ways to build a web store, presentation, or landing page without writing a line of code.

So, what opportunities will arise from that? If you learn to use a good website building tool better than most people, you can excel and get a lot of projects done quickly. Add to that some coding skills and some design knowledge, and you have yourself a decent career in the making.

But, can you do better? Yes, you can, by focusing on what can’t be automated. For now, solving complex problems with code can’t be automated. A website builder can generate a web page, but it can’t generate, for example, a stock market analysis platform. Even if artificial intelligence grows so clever that it can code anything, it will still need to first understand what it is that the client wants to build. “Build a stock market analysis platform” is not a viable command for a machine. You need to provide exceedingly detailed project specifications before even the smartest robot can begin to comprehend what it needs to do. Even then, it’s not enough. If there is one thing experienced software developers know, it is this: no project spec is ever good enough. Every specification document needs to be discussed, revised, revamped, refactored and, sometimes, tossed out to be replaced with something that makes sense. So, where does that bring us in our career quest? Project management, creativity, and communication are more things that are difficult to automate and therefore have a future.

But wait, the rabbit hole goes deeper. What if computer-brain interfaces become very advanced in the next couple of decades? This could spell the end of the middle-man. The moment thoughts can be translated into code is the moment that programming dies. The good news is, I highly doubt that this will be a problem for your generation. If and when it does, it will open some amazing doors — new possibilities, new products, new ideas, and entirely new modes of living. Jobs will never disappear unless the economic need for people to work disappears.

The entire flow of thought above can be modified for your desired industry. List the jobs you would like to have within this industry, then walk through the algorithm, step by step. Eliminate the jobs that are likely to be an automation dead-end, compare the others, and make an informed decision for the robot era.

Not all industries are created equal, however. Areas such as space exploration, energy, and robotics will be the focal points of the upcoming decades. Space-related business in particular is likely to take off (no pun intended) at an unpredictable pace, which might just catch most of us off-guard. From relatively simple space tourism to very un-simple asteroid mining, there is a myriad of star-lit ventures we will have the pleasure of observing in the coming decades. Some of you will have the pleasure of participating in them, and some within that group will make fortunes.

As a parting thought, keep this in mind: what is happening now is nothing new. Ever since the beginning of the industrial age, automation has been destroying jobs and creating new ones. We all have to deal with it one way or another. The only choice is: do you want to be prepared to work with robots, or do you want to try to fight them?