By Anthony P. Carnevale and Artem Gulish

Recent protests in metro areas across the United States taking place against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic have drawn much-needed attention to police brutality and other forms of systemic racism. Among these forms of racial injustice are entrenched economic disparities among racial groups. This economic injustice is reflected in decades of unequal employment and wage growth, fueled by centuries of racism and prejudice, and underpinned by an unjust education system masquerading as a meritocracy. After a decade of improvements in Black Americans’ economic circumstances since the Great Recession, this injustice has been laid bare once again with the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Data from the Household Pulse Survey, a weekly data collection by the US Census Bureau designed to assess the ongoing impact of COVID-19, clearly demonstrates the unequal effects of the COVID-19 crisis on Black Americans’ economic status compared to that of White Americans. Since coronavirus-related business shutdowns began in March, 56 percent of Black adults have experienced a loss of employment income in their households, compared to 43 percent of White adults — a 13-percentage-point gap (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The share of Black adults with loss of employment income in their households is 13 percentage points higher than the share of white adults.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the US Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, May 21–May 26, 2020.

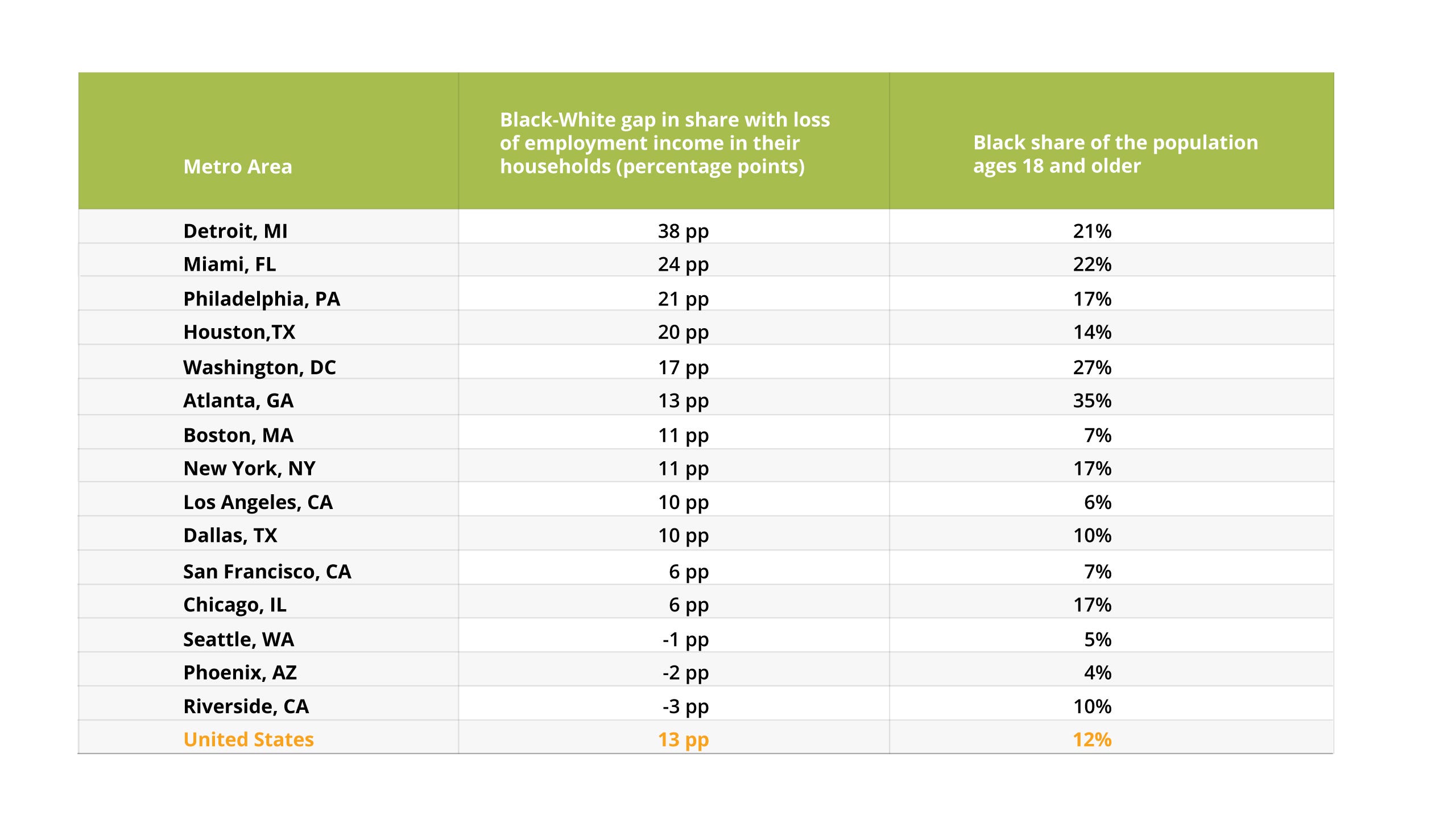

In some major metro areas that have seen protests in recent days, including several where Black adults represent a relatively large share of the population, the Black-White gap in lost employment income is much larger than for the country overall. In the Detroit metro area, which was still reeling from the Great Recession when the COVID-19 crisis hit, the Black-White gap in loss of employment income is 38 percentage points, with a shocking 85 percent of Black adults have experienced such a loss. In the Miami metro area, where Black adults account for 22 percent of the adult population, the gap is 24 percentage points. In the Philadelphia metro area, the gap is 21 percentage points. In the Houston metro area, it is 20 percentage points. And in the nation’s capital — the Washington, DC, metro area, where Black adults account for more than a quarter (27%) of the adult population — the Black-White gap is 17 percentage points, 4 percentage points higher than for the country overall (Table 1).

Table 1. Of the 15 largest metro areas in the United States, 10 have double-digit percentage point gaps between the share of Black and White adults that experienced the loss of employment income in their households, including some of the biggest metro areas with high concentrations of Black adults.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from US Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, May 21–May 26, 2020.

Note: Positive gaps in the share with loss of employment income in their households indicate that a larger share of Blacks than Whites have lost employment income since March, while negative gaps indicate that a larger share of Whites than Blacks have lost employment income in the same period.

These economic disparities, exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, must be addressed as part of a systemic approach to dismantling racism and inequality in the United States. Equalizing economic opportunity will require a multipronged approach that includes improving access to successful pathways to and through higher education and the labor market while addressing discrimination and prejudice in all areas of American life. In many of America’s largest metro areas, which have long struggled with the persistent legacies of racial segregation in housing and the labor market, the call to action is clearer than ever. And leaders and decisionmakers all across the country must realize that messages of sympathy and solidarity are constructive, but what really counts is action.

Dr. Carnevale is the director and research professor and Artem Gulish is the senior policy strategist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. CEW is an independent, nonprofit research and policy institute affiliated with the Georgetown McCourt School of Public Policy that studies the link between education, career qualifications, and workforce demands.

Follow the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce on Twitter (@GeorgetownCEW), LinkedIn, YouTube, and Facebook.