Because it was a nice afternoon in March, Katrina Llorens Joseph and her husband Albert decided to sit outside for lunch at the Subway restaurant not far from City Park.

Afterward, she went back to her desk at the VA Hospital, and he got behind the wheel of a city bus.

“He dropped me off at work and then he went on to work,” she said.

As routine as the lunch was, it now seems like a fateful one to Joseph, 52. The couple had been very careful about isolating. She believes her husband, 53, came in contact with the virus that day at an emergency meeting with a bunch of other bus drivers. Within a few weeks, 1 in 8 Regional Transit Authority employees would test positive in a COVID-19 outbreak that led to the deaths of three workers.

Days after that lunch, Albert Joseph left work early, suffering from fevers, chills, and a high fever.

His wife snapped into action. “I figured he had the virus,” she said.

Katrina Joseph moved to the guest room. She began wearing a mask in the house, pulled out new toothbrushes for everyone, wiped down doorknobs, washed her hands, and served food on paper plates.

Even so, the whole family became infected. For the next few weeks, the couple and their daughter, Danielle, 19, were all bedridden in separate rooms of their house in Chalmette. They spiked 104-degree fevers. Sometimes, they collapsed on the way to the bathroom. On four separate occasions, when fingertip monitors indicated dangerously low oxygen levels, they called 911, though the ambulances twice left empty.

Once, paramedics took an oxygen-deficient Albert Joseph to the hospital for a four-hour stay. The second time, they carried out a very weak Katrina Joseph. She spent eight days in Ochsner Health Center in St. Bernard Parish, “lying there, knowing that I had this disease that was killing people all around me.”

The Josephs’ story is hardly unusual. But leading researchers say their experience and others like it offer a window into why the coronavirus has hit Black communities particularly hard across the nation. Many frontline workers who continued to work through the pandemic were exposed on the job and brought the virus home to infect entire households.

Workplace spread a driver

Within Louisiana, Blacks have accounted for nearly half of all COVID-19 deaths to date, despite making up a little less than a third of state residents. The biggest reason for the coronavirus’s cruel toll in Black communities seems to be its outsized infection rate there: when compared with White Louisiana residents, Black Louisianans have been three times as likely to contract the virus.

A new, much-discussed study concluded that the disproportionate spread in the Black community originates in the workplace. The massive study, encompassing data from 100,000 patients, was conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, part of the National Institutes of Health, and published last month Sept. 17 in Health Affairs, the prominent health-policy journal.

In hopes of further understanding COVID-19’s racial and ethnic disparities, researchers took a look at the role of common hypotheses, including underlying health conditions, that have been offered as explanations for why the virus has ravaged African American communities.

After running a number of analyses, researchers concluded that their data suggests pre-existing conditions are not key drivers of the disparity in coronavirus deaths. Instead, it indicated Black and Latino's workers were more likely to get infected on the job than Whites, and that they typically return home to larger households, magnifying the inequity.

“We believe that COVID-19 disparities will ultimately be shown to stem from disparities in exposure, such as the dimensions of employment and household transmission we examined,” the study concludes.

Close examination of COVID-19 case data also yields evidence of what former OSHA head David Michaels calls “the impact of work.” The median age of Black and Hispanic people who tested positive for COVID is much lower than that of Whites because they are working-age people, infected on the job, said Michaels, now a professor at George Washington University, who co-authored a paper on the topic, published last month in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The disproportionate spread in Black and Hispanic communities stems from on-the-job exposure, said Michaels, who describes the pandemic as “an unprecedented, massive worker-safety crisis.”

Essential and frontline workers

From the start, the coronavirus was rooted in worker illness, starting with the workers at the seafood market in Wuhan. According to a study of COVID-19’s early spread in six Asian counties, nearly half of the early outbreaks of the virus originated in the workplace.

In New Orleans, cases rose so quickly after Mardi Gras that there was little way to trace their origins, said Dr. Jennifer Avegno, who heads the city’s health department. “I think the virus was so widespread early on that who knows where you got it. Was it a parade? Was it your work? Was it at your mama’s house?”

But in other cities, researchers have found that the virus took hold mostly in neighborhoods with the greatest concentrations of frontline workers: healthcare workers, first responders, and those who work in hotels, restaurants, and music clubs.

“Workers in the hospitality and entertainment industry, where low-wage workers are over-represented, are at far greater risk than office workers and professionals, who can work from home or otherwise control their work environment,” said Michaels, the former OSHA administrator.

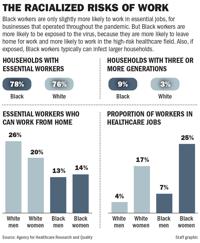

Parsing the data goes beyond determining who is considered an “essential worker.” National and local data, like that published by the Data Center in New Orleans, showed that Black workers nationally were only slightly more likely to be deemed “essential” — in other words, employed by businesses that stayed open during the pandemic.

But researchers for the Health Affairs study found much larger gaps in who could work from home.

Nearly 26% of White men and nearly 20% of white women who were characterized as essential could work remotely, compared with 14% of Black women and 13% of Black men. On top of that, when looking at workers overall, 25% of all Black women worked in the high-risk health sector, versus 17% of White women, 7% of Black men, and 4% of White men.

And even those estimates don’t capture the full picture, since most such studies don’t include cash-business workers who may not be deemed “essential” but can’t afford to stay home, said Alfred Marshall, an organizer for STAND With Dignity. Though little data exists, Marshall says this group is disproportionately Black and Latino.

“If you add the... guys who wash cars or sell food from trucks, the count of at-risk workers goes up significantly,” Marshall said. “These guys are frontline workers and they can contract the virus, without a doubt.”

Ernest George, 35, a laid-off ironworker who lives in an apartment building on Chef Menteur Highway, said most of his neighbors have worked through the pandemic, including a man who lived three doors down. “He was a carpenter, who went to work with his tools every day,” George said. “The pest-control guy came and found the man dead.”

Neighbors said he died of a heart attack but that he also had COVID.

George does not know the man’s name and the coroner’s office had no record of someone dying from the coronavirus at that address. But when a team in hazmat suits came to get the man’s body, it sent a ripple of fear through the complex.

“It really shook me,” George said. “I used to get people calling me, asking me to fix this or that in their homes. But after my neighbor died, I said no to those little jobs. The work just seemed too risky.”

Vectors of spread changing

Early on, some public-facing workplaces did not support the use of PPE, thinking that it would scare off customers. A local doctor who handles high-risk pregnancies recalled calling the owner of a daiquiri shop because a pregnant patient who worked there wasn’t allowed to wear a mask and gloves.

Much of that original resistance has given way.

But worker advocates note that many people still fear blaming their employer for the spread of the virus, lest they lose their jobs. A survey by the National Employment Law Project found that Black workers were twice as likely to report being punished for speaking up about COVID-19 exposure at work. Self-employed people, such as maids and gardeners, who may have caught the virus from their employer or from contaminated surfaces within an employer’s home, maybe especially reluctant to make waves.

Since the pandemic began in March, a long list of outbreaks – in Louisiana and around the country -- have been traced entirely to employees infected while on the job. Often, these hotspots are in workplaces where employees stand close to one another or touch shared equipment.

The state has noted outbreaks in 27 food-processing facilities and 58 non-food facilities that ship, package or produce chemicals, plastics, oil, gas, processed wood, or machinery. Additional flareups, though fewer in number, were reported within other Louisiana industries: towing, welding, aerospace, drilling, glass, jewelry, and waste disposal.

In some workplaces, state investigations have found that both staffers and customers were infected. In the seven casinos and 41 restaurants where outbreaks occurred, only about half of those sickened were employees; the others were patrons.

Though Albert Joseph, the bus driver, was infected in March, his case has similarities to recent outbreaks traced by the state’s health department. If his wife’s theory is correct, he was exposed not while driving the bus, but while gathering with other drivers for a meeting.

His exposure still is a result of his status as a frontline worker. But it isn’t necessarily tied to his day-to-day duties.

Many investigations into workplace outbreaks find that workers are infected by co-workers, not by customers, said Theresa Sokol, the acting epidemiologist for the Louisiana Office of Public Health.

A study of Houston healthcare workers reached the same conclusion about spread within a hospital after finding an “odd pattern of infections” among a group of workers whose jobs didn’t overlap. They traced all of the COVID-positive employees to “off-stage areas” like break rooms.

In Louisiana, workers are increasingly better protected from the general public, thanks to plexiglass barriers and medical masks, Sokol said. They are more likely to be exposed when off-duty and unmasked, eating lunch together in break rooms, taking cigarette or phone breaks, or riding in a carpool, or talking during an after-work social hour.

Avegno is seeing the same phenomenon in other settings, like colleges.

“Transmission isn’t happening when college students are sitting in their lecture hall, socially distanced, wearing a mask, listening to a professor. It’s happening when they are having their parties off-campus or going to a town where bars are fully open,” Avegno said.

Sokol noted that group cigarette breaks seem tailor-made to spread this virus. “You’re not wearing masks; you’re exhaling respiratory droplets and blowing them farther than you would if you were breathing or talking normally,” she said.

Before Tulane University re-opened, industrial hygienists assessed every building on campus for risk, said Thomas LaVeist, dean of Tulane University’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. That kind of assessment might be impossible for smaller businesses and mom-and-pop shops, but the idea is crucial, he said.

“To maintain safety for every worker, we need to think about stairwells, elevators, lunchrooms, and every place where a person might be,” LaVeist said. “If we’re going to see another outbreak, it will likely occur because of workplace spread. And this is where inequities come in. Because who is more likely to work in those workplaces?”