Yessenia Cendejas pulled up to a moving truck filled with donated food in northeastern Wisconsin, arriving at the mobile food bank straight from her job at a pizza-crust factory, to get sustenance for herself and five children.

Cendejas, 35, took a second job at a fast-food restaurant in Green Bay - whose county has Wisconsin’s highest number of COVID-19 cases per capita - after her factory employer reduced her hours, but says her income is now half of what it was.

“There were times we couldn’t work, so it was tough,” she said. “I’m more stressed out. You start thinking, ‘What do I do?’”

As hunger rises in America, the Trump administration’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout is under scrutiny ahead of the Nov. 3 election that could be decided by hotly contested Midwestern states like Wisconsin.

U.S. President Donald Trump has funneled a record amount of aid to the agricultural sector, the majority going to big farms over food workers or small-scale farmers. Cendejas has already voted - for Trump’s Democratic challenger, Joe Biden.

Just 15 miles (24 km) from where she picked up her food, a large-scale corn and soybean farmer received $1 million in coronavirus aid from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the largest amount in the state, federal data shows.

Crusaders of Justicia, the Manitowoc, Wisconsin-based food relief organization that served Cendejas, has gone from serving 125 families a year to more than 3,000 in 2020.

Meanwhile, more than 54 million people in the United States could struggle to afford food during the pandemic, with the biggest increases in food insecurity in North Dakota, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, according to Feeding America, a network of 60,000 U.S. food shelters.

More people who harvest food, work in food processing, and even own their own farms now need food assistance, according to dozens of food bank workers nationwide.

“A lot of these farmers have just had so much pride that they never thought about taking that trip to a local food pantry,” said Melissa Larson, who manages food programs for seven counties in northwestern Wisconsin.

The Trump administration has paid farmers nearly $18 billion in direct payments since June through its Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), but nearly 92% of farmers in Wisconsin received less aid than it costs to run an average dairy in the state for a month, according to a Reuters analysis of federal USDA data.

Biden leads Trump by a margin of 53% to 44% in Wisconsin, a Reuters/Ipsos opinion poll showed on Monday. Trump won the state in 2016.

Visitors to U.S. rural food banks declined in June, likely due to federal aid such as stimulus payments to all Americans, expanded federal unemployment benefits for laid-off workers, and the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program.

By mid-August, aid ran dry and families again faced empty cupboards as COVID-19 cases increased in the Midwest. Rising crop and livestock prices bled into grocery stores. The cost of bread jumped nearly 20% in June, while meat increased 17%, according to market research firm Nielsen.

LIMITED REACH

Much of the federal aid to farmers, however, is not reaching many agricultural workers, as the program does not stipulate protection for farm employees, said Diana Tellefson-Torres, executive director of the UFW Foundation, a farmworker advocacy arm of the United Farm Workers Union.

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said CFAP is meant to keep food on Americans’ tables and the program is limited to $250,000 per farm owner.

“Larger farmers in the United States produce 80% of the food. That’s why the money goes there,” added Perdue, who spoke while visiting a dairy farm in Cedar Grove, Wisconsin, in October.

The Trump administration and U.S. lawmakers have been unable to agree on additional stimulus. The agriculture department has distributed 9.5 million food boxes since June under a program meant to funnel food quickly to those who need it, but food pantry workers say it will not be enough.

MAKING ENDS MEET

In Elkhorn, a town of 10,000 in southeastern Wisconsin, 30 cars stretched down the block to the Walworth County Food Bank in early October, a half-hour before opening.

By day’s end, more than 100 families picked up food, including Matt Hausner, a local grocery store employee.

“I’ve still been working full-time, but it doesn’t make all the ends meet,” he said. “Every couple of months, I find myself having to come here.”

Hausner, who does not plan to vote, said the grocery store is busier than normal after the pandemic closed restaurants and drove Americans to stockpile groceries. But he has not seen a pay raise.

Weekly survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau and an annual study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture show that hunger is rising, particularly in rural states, after a decade of decline. By late September, Vermont, West Virginia, and North Dakota topped the Bureau’s list, with a more than 50% increase in respondents saying they lacked enough to eat.

“The underlying issues that always made rural hunger a problem have been exacerbated with COVID,” said Tracy Fox, president of Food, Nutrition & Policy Consultants LLC, an advocacy and policy research organization, citing transportation, families taking in relatives, and lack of affordable housing.

Austin Wall, co-owner of L & W Farms, received just $10 from the first round of the USDA’s direct payments, the smallest amount in the state. Wall, 24, farms more than 200 acres of corn, soybeans, alfalfa, hay, and apples in northeastern Wisconsin’s Shawano county.

“That didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me,” said Wall, who estimates selling 25-30% fewer apples to local schools and restaurants during the pandemic. After voting for Trump in 2016, Wall said he is undecided in this election.

The farm received $6,600 in the second round of CFAP payments which started on Sept. 21. The aid will cover expenses for a few months, but Wall said he is facing more losses as winter farmers’ markets, normally held indoors, close.

“That’s going to hurt us a good amount. I’m not sure what we’re going to do,” he said.

The voters of Monroe County, Michigan, may have expected an economic windfall when they flipped from supporting Democrat Barack Obama to help put Donald Trump in the White House in 2016.

But it went the other way: Through the first three years of the Trump administration the county lost jobs and brought in slightly less in wages in the first three months of 2020 than in the first three months of 2017 as Trump was taking over.

And that was before the pandemic and the associated recession.

With the U.S. election just a week away, recently released government data and new analysis show just how little progress Trump made in changing the trajectory of the Rust Belt region that propelled his improbable rise to the White House.

While job and wage growth continued nationally under Trump, extending trends that took root under President Obama, the country’s economic weight also continued shifting south and west, according to data from the U.S. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages that was recently updated to include the first three months of 2020.

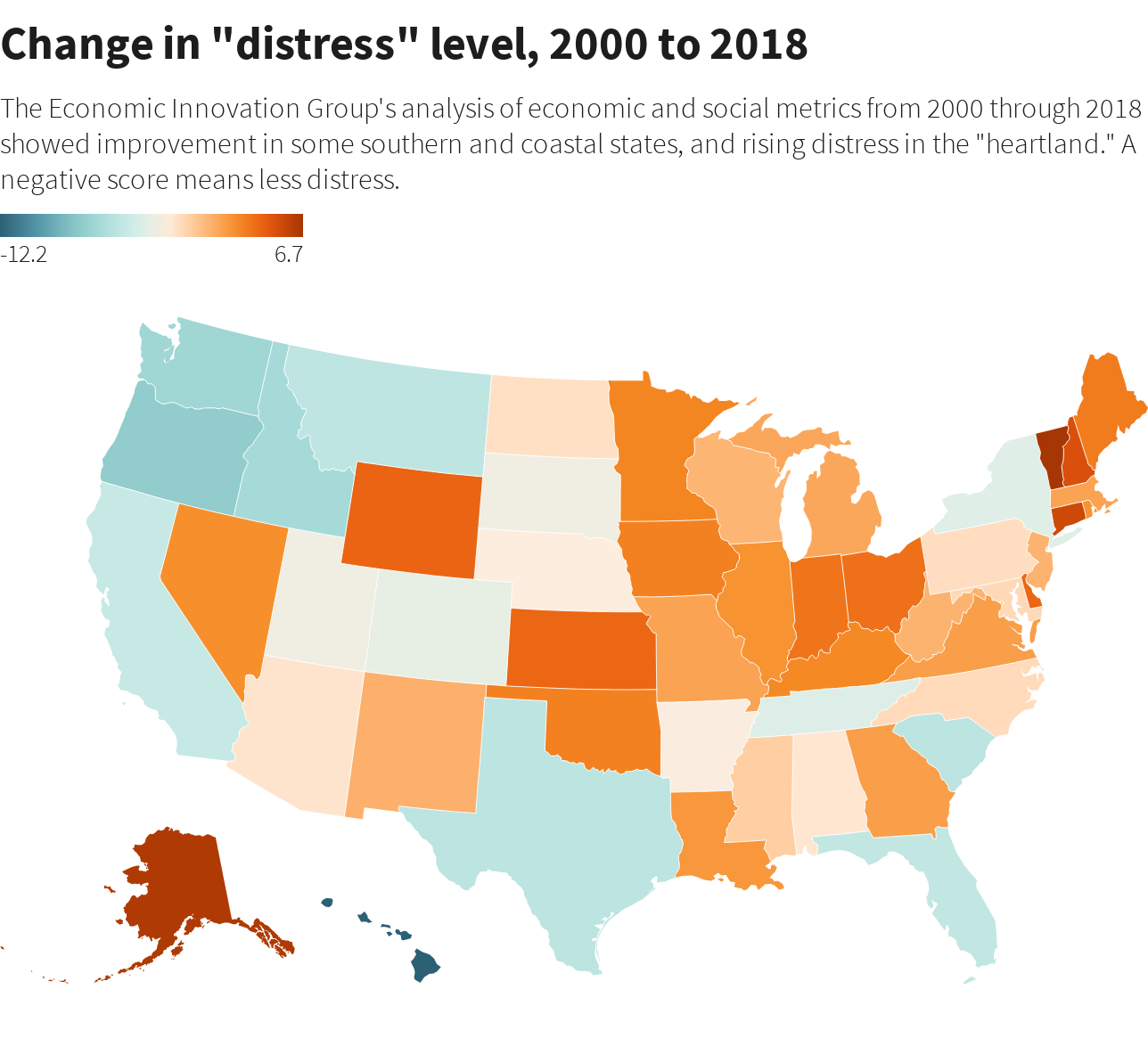

A recent study from the Economic Innovation Group pointed to the same conclusion. It found relative stagnation in economic and social conditions in the Midwest compared with states like Texas or Tennessee where “superstar” cities such as Dallas and Nashville enjoyed more of the spoils of a decade-long U.S. expansion.

Graphic: Job growth under Trump

LAGGING THE COUNTRY

Across the industrial belt from Wisconsin to Pennsylvania, private job growth from the first three months of 2017 through the first three months of 2020 lagged the rest of the country - with employment in Michigan, Wisconsin and Ohio growing 2% or less over that time compared to a 4.5% national average, according to QCEW data analyzed by Reuters.

Texas and California saw job growth of more than 6% from 2017 through the start of 2020, by contrast, while Idaho led the nation with employment growing more than 10%.

Perhaps notably for the election, a Reuters analysis of 17 prominent counties in the five battleground states of Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin showed the limits of Trump’s controversial tax and trade policies in generating jobs where he promised them. All 17 of the counties had a voting-age population greater than 100,000 people as of 2016, supported Obama in the 2012 election, and voted for Trump in 2016.

In 13 of those counties, all in the Rust Belt region, private job growth lagged the rest of the country. Employment actually shrank in five of them. Of the four with faster job growth than the rest of the country, two were in Florida, one was in Pennsylvania and one was in Wisconsin.

The findings show that under the “greatest economy ever” boasts that Trump made before the pandemic, when job and wage growth were indeed strong, the fundamental contours of regional U.S. prosperity seemed largely unchanged.

Some of that may have stemmed from Trump’s own policies. The use of steel tariffs, for example, may have ended up costing Michigan jobs.

“The key battleground areas...have not fared well under President Trump, even prior to the pandemic,” said Moody’s Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi. The swing state counties most supportive of Trump in 2016, he said, were “especially vulnerable” to the president’s trade war tactics because of their ties to global markets.

Graphic: Manufacturing jobs under Trump

DRAMATIC SHIFT

But Trump was also swimming against a very strong tide, driven by forces bigger than a Tweet or a tariff can likely counter. For decades people, capital, and economic output have been shifting from a mid-20th century concentration in the U.S. Northeast and Midwest to the open land, cheaper wages, and more temperate climate of the Sun Belt, and the innovation corridor from Silicon Valley to Washington state.

Trump, in his 2016 campaign, put a premium on manufacturing jobs - last century’s path to the middle class - and as president used a combination of trade policy, tariffs, and blunt force arm-twisting on companies to try to shore up the prospects of the industrial heartland that formed his electoral base.

It didn’t happen. Texas, according to QCEW data, gained more manufacturing jobs from 2017 to the start of 2020 than Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania combined; the smaller but increasingly competitive manufacturing cluster in Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama gained as many factory positions as those legacy manufacturing states.

While Trump may have failed in his efforts to reinvigorate the Rust Belt, the forces acting against the region pre-date his administration.

A longer-term analysis by the EIG, looking at outcomes across an index of social and economic measures, showed little progress from the start of the century through 2018.

According to a Reuters analysis of EIG data, two to three times as many counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin slipped further down the think tank’s Distressed Communities Index as climbed to a more prosperous bracket over those nearly two decades.

In Florida and Washington state, by contrast, five times as many counties moved into a more well-off bracket, and in California, three times as many counties prospered.

Graphic: Change in "distress" level, 2000 to 2018

EIG research director Kenan Fikri said it was “easy to forget” that the Midwest and Great Lakes regions were once the “pinnacle of what the U.S. had to offer” before the economy shifted to a more tech, service-oriented and global footing.

“We have seen the gravity of economic wellbeing take a dramatic shift to the west ... It continued unabated through the first several years of the Trump administration,” he said.